In the upcoming third chapter of Only by the Grace of the Wind, “Vive Memor Leti,” Karina Bergson’s life…changes. Without committing the grave sin of spoiling, I can say only that these…developments…act as a fulcrum against which the rest of the story arcs and shifts. Soon, I think you will have a better sense of what I mean, but in the meantime, I wanted to share a few stray thoughts about memory and time.

There is something transcendent about memory, along whose threads we can travel through time. Though mine is by no means eidetic, I have always been able to remember. Names, places, stories, minutiae that have no business being so sticky—if I’ve slept well, I can usually summon them from the abyss. And if I haven’t, there are the taunting anamnestic mists, the almost-there shells of recall that haunt me until the memory launches itself into awareness.

I still have a primordial vision, fuzzy as the opening moments of an overplayed VHS tape that’s been left in the sun, of glimpsing my newborn brother Matt in the hospital nursery. It shouldn’t be possible. I was not quite two years old. And yet, I have a firm, unchanging recollection of an attempt to scramble onto an overpainted institutional sill to look through the leaded nursery window. Eventually, my dad had to lift me up so I could mark the intruder who would soon come home with us. The memory ends with the window, opaque now in strained remembrance. Is this a confabulation? Or a false memory? Did one of my parents simply tell me a story with which I conflated an actual recollection? All I can say is that even this first memory is suffused with sensory observations: the sticky window sill, the antsy frustration of inhabiting an uncooperative toddler body, the wordless jumble of emotions that I couldn’t—and still cannot—parse.

Even now, as I push forty, I can still recollect significant, contiguous swaths of my early childhood. More than that, like a child in a Wordsworth poem, I still have a composite felt sense of what it was like to be the person in those memories, when time seemed to stretch along an endless horizon and the novelty of discovery invited wonder where something more mechanized and tedious now lives. I can, you might say, still remember the other Bens who once resided within this body, the succession of slightly different Bens who were once the experiencing subject, me.

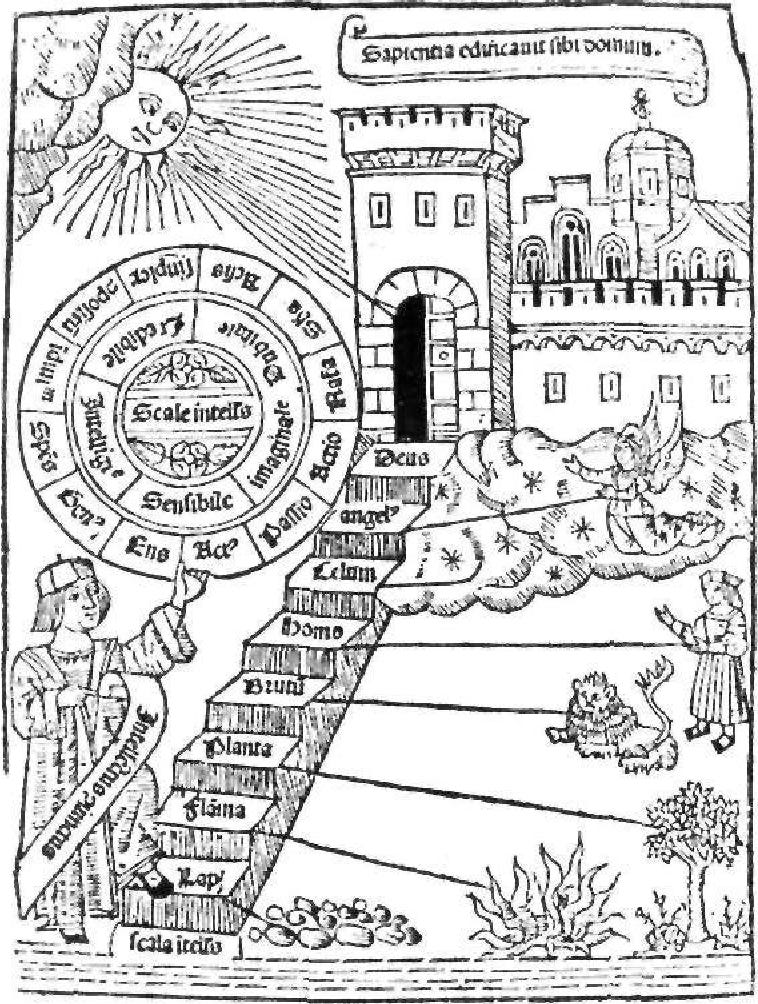

In her groundbreaking book, The Art of Memory, the eminent 20th-century British historian Frances Yates outlines a metaphysics of recollection that makes our current discourse (“your brain is like a computer”) seem hopelessly dull and banal. For classical philosophers and Renaissance heretics alike, memory was a sublime conduit between the self and the cosmos. Yates is most known for her work uncovering the life and influence of Giordano Bruno, a 16th-century hermetic philosopher and mystic burned alive by the Catholic Inquisition. He believed that the reflection of the whole universe was mapped onto the human mind, and a singularly subtle, supple memory could reveal “the all in the all.” The art of memory lay in the careful, deliberate cultivation of memory through mnemonic training, dilating the elastic human capacity for remembrance as a means of communing with God and the self. This method, which has been immortalized by the BBC series Sherlock and even the historian Tony Judt, is part of a tradition stretching back into antiquity.

It is a form of “inner writing” that goes by many names. Here, we will call it the method of loci, and it is quite simple to learn. Here is a sneak peek from the next chapter of Only by the Grace of the Wind, “Vive Memor Leti,” in which Karina’s father offers this explanation

“Find solace somewhere quiet - an empty room or a secluded meadow. Close your eyes and imagine a place, real or fanciful, city, structure, or path. It will unfold as you imagine it, and to each feature, or locus, attach something you wish to remember. This could be a signpost, a chest of drawers, a building, a tree. Anything, Karina. Imagine yourself exploring this space. Label your loci. Explore some more. Soon, your place will be thick with the material of memory, which will return to you in vibrant recall when you stroll through the landscape you have made. The possibilities for these mnemonic panoramas are truly endless. Hide away there when circumstances demand it…”

Put simply, the method of loci uses space, imagination, and movement to encode and retrieve information. One imagines a structure or landscape and assigns memorial items to features (loci) within this space. So, for instance, let’s say I conjure a foyer filled with boxes of varied colour and appearance. Inside the red box, I drop a note with the number 828 printed on it. On top of the blue box, I place a rock etched with the number 497. And at the bottom of the yellow box, I tack a scrap of fabric to the wall that reads 4459. Now, when I tour this room in imagination space, I will come across the red, blue, and yellow boxes, whose contents provide a ten-number sequence, 828-497-4459 (in this case, a totally bogus phone number).

Using a much more intricate version of this mnemonic tool, our forebears demonstrated an astonishing capacity for remembering. Though the method was originally employed to memorize speeches, the most skillful and adept could remember whole books. This sort of memorial engagement is, according to Socrates, perhaps the only true way of knowing anything at all. In Plato’s Phaedrus, the old gadfly warns against the verisimilitude of writing, which exists outside of oneself and thereby produces only the appearance of knowing.

The contemporary Italian physicist and philosopher Carlo Rovelli believes that human memory has a more cosmic purpose. In his book, The Order of Time, he writes that it is a concatenation of traces time’s passage leaves on our bodies—indeed, the very synapses connecting the neurons in our brains:

“Memory, in its turn, is a collection of traces, an indirect product of the disordering of the world…the one that tells us that the word was in a “particular’ configuration in the past, and therefore has left (and leaves) traces…we are stories,” (Rovelli, 163).

We are, he suggests, histories of ourselves. “I” as I am now exist because of memory, which is the glue that binds my “Ben-ness” together. It is why “I” of today is the same as “I” of yesterday. To understand myself, then, is to understand the peculiar and particular ways in which the passage of time has tattooed my memory. We can see traces outside of the self, in the world around us, but the flow of time is experienced in us, in moments that leave marks in our apprehension and psyche as memory and anticipation. “Time,” Rovelli writes, “is the form in which we beings whose brains are made up essentially of memory and foresight interact with the world: it is the source of our identity…and suffering as well.”

These memories are our stories, the unique and particular latticeworks of traces time inscribes upon us in the language of memory. In this view, each moment is a poem, each day a saga. Life ebbs and flows. We shift and change. Some traces fade while others glow and pulse. It is ineffable, this experience of lived time, and perhaps no one gets closer to capturing its lyricism than Nobel laureate and French philosopher Henri Bergson.

In his Creative Evolution, he writes (emphasis my own):

“The past is preserved by itself, automatically…probably, it follows us at every instant; all that we have felt, thought and willed from our earliest infancy is there, leaning over the present which is about to join it, pressing against the portals of consciousness that would fain leave it outside…memories, messengers from the unconscious, remind us of what we are dragging behind us unawares…” (Bergson, 5).

Our ineluctable, tidal memories are so precious, even when they take the form of anguished eruptions, for they are a record of time’s impressions on this one—yes, you!—which never again can be. I have titled this dispatch “Live Remembering Death,” the English translation of the Latin Vive Memor Leti. Cliche or not, we too shall pass. And our time, and thereby our memories, will (likely) fade with our bodies. That seems to be the grand guarantee.

The ancients believed that memory was a gateway to the sublime. When my inner aperture is open and squeegeed, my recollections, even the bad ones, can be a source of awe, a window into a story not read but lived. I remember, therefore I was. I remember and I still am. Karina remembers, too, though for her, as you will soon see, memory is about to become something more fraught and uncanny.

And, I should acknowledge, for some, memory is not so much a gateway as a prison, not the stuff of treasured remembrances but a sort of violence visited upon an aching psyche as hauntings. There are things that can happen to a human being that leave traces that burn and shriek. In contemporary discourses of trauma, certain memories must be “restructured” and “rescripted” to permit relief. The traces time has left can be unbearable, too. Like footprints in the sand, we hope, maybe, that some of them can be brushed away.

But there is also a certain species of memory that I wish I could, by some transitive property, share with a beloved other. Not just the sights, sounds, and smells that permeate the recollection, but also the felt sense of what it was like to be there, then, and me. It is a deeply intimate impulse, a longing for a kind of sonder that we, as humans, can only glimpse in the most beautiful moments of shared experience, the fusion of two seeking souls.

This yearning to show another the traces time has left is, at root, a desire to give a piece of yourself to another. It isn’t possible, as far as we know.

And yet, what if it was?

Fig. 4: The Ladder of Ascent and Descent. From Ramon Lull's Liber de ascensu et descensu intelkctus, ed. of Valencia, 1512 (The Art of Memory. Ian M. L. Hunter and F. A. Yates, 1967)

What an interesting read! I'm looking forward to chapter 3.