Welcome back to Only by the Grace of the Wind, a slightly surreal novel presented in twelve serial chapter instalments released every Monday morning.

In an effort to expand my readership, this chapter will remain free to read. Please don’t forget to like, comment, and share!

Feeling lost? You can get your bearings by visiting the Table of Contents

My parents’ squat little bungalow, with its pitched roof and chipped heather paint, sits empty now. I arrive early, a full hour before Ben, and let myself in through the flimsy back door, which the real estate agent has magnanimously left unlocked. Just as I used to, I launch my tote onto the kitchen floor from the arched rear doorway and dangle my legs down the stone steps, gripping the cool metal railing with both hands, daring it, maybe, to pull loose from the wall once and for all in a final strident surrender.

Perhaps I should not be surprised that this modest mid-century sold so quickly. One would be hard-pressed to find a more central urban node than the Saltspray neighbourhood, situated as it is at the outer reaches of the trendy Bonneville core. But when my parents settled here in the early eighties, it was staid, almost sleepy, a residential block peopled with young families clinging to society’s middle rungs.

Now, evidently, the house is being marketed as a teardown for thirty-something Californians with designs to carve it into a quadplex for hapless students priced out of the dorms. Vacant and denuded of furniture, the beveled square rooms have a forlorn quality. I cannot bring myself to go on a farewell tour. My loose ends are plenty frayed. The real estate agent hired a moving company to box up our family effects and cart them to the Storage Bunker, so only the hobbled spectres of memories remain. For old time’s sake, I sit cross-legged on one of the cool stone steps in the darkened rear stairwell, stamping the soles of my flats every now and then, waiting for Ben, my interlocutor.

When he rings the doorbell, I hoist myself up and give my tote a little kick. I jog through the barren living room, which seems so much larger without the sagging couch and heavy antique furniture, and yank on the front door.

My Torquemada is standing cross-footed on the landing, a paperback notebook cosseted under one arm. We share a small kiss.

“I feel like one of those celebrity skeptics that comes on TV every now and then to disgrace a spoon bender.”

“Yeah, whatever,” I say, motioning him into the vacant living room. “You know what I forgot? Chairs. I have to figure out where we can sit.”

I whisk down the narrow hallway, past the kitchen, and up the stairs to peek into the two bedrooms, whose only adornments are little asterisks of fluorescent masking tape marking dents and gashes in the wall paint. Then I rumble down the staircase again to appraise my parents’ offices.

My mother’s oblong nook is empty aside from a single empty black trash bag with crumpled paper cradled like eggs in one of its plastic hollows. In my father’s office, there are three taped cardboard boxes clustered in the entryway. I kick them lightly to assess their contents, and not a one budges. They are heavy and solid, full of books, I imagine, the last of the bygone Bergsons. I make a mental note to mention this packing oversight to Barry, who will pass it along to the real estate agent.

It is a poignant irony that it is here, at the site of my inaugural turning, that I will expose this most baroque of secrets. Here in my father’s erstwhile haven, where he tapped out his epistolary manuscript, his various valedictions to be distributed to his intimates, and then forgot about them. What would he make of this dubious spectacle I am orchestrating? This bit of exhibitionism.

I hear Ben venture out into the hallway, his boat shoes cheeping on the hardwood floor.

“I found something,” I call to him.

He meets me at the doorway of my father’s office and cranes his neck to look in.

“I have to get the stuff,” I say, and edge past him. The tote bag is still sprawled out on the kitchen floor in layered folds of desiccated pleather. I had loaded the talismans with exaggerated care and let the airy bag dangle from two fingers on the walk from my apartment to my parents’ house. Now, I edge the bag out of the kitchen with a vengeful foot, punting it along the hardwood in skidding swishes. Ben’s voice rings out into the hallway.

“Hey, do you need help or anything?”

I pivot when I reach my father’s office and boot the bag into the centre of the room. “No, no,” I say. “We’re all set.”

“They’re in there, aren’t they?”

I nod. “Oh, shit. I didn’t get us food or drinks or anything,” I say.

Ben reaches across his abdomen to swing around a canvas messenger satchel, which I had not noticed in my frenetic haste. “I have a big water bottle,” he says. “We can share.”

Using the sole of my trusty flat, I shove the two laden cardboard boxes from the doorway into the centre of the room, where Ben arranges them such that we can sit facing each other. He plunks down on one and lays his bag upright on the floor.

“Jesus, you could make a cup of coffee nervous,” he says.

I sigh and straddle the other box like a saddle, both legs hugging one of the vertices. “Well, this is stressful,” I say. “I’m really putting it all out there.”

He eyes me sidelong for a moment, as though sizing me up. “You’re really serious about this.”

“Why would I lie?” I snap.

Ben holds up an appeasing hand. “I’ve never been much for the occult.”

“Well, me neither.”

“And,” Ben says slowly. “I’m maybe a bit surprised. I wondered whether this was, I don’t know, some sort of romantic ploy. A sexy practical joke, maybe.”

“A sexy practical joke,” I echo with a scornful, breathy hiss. “Look, we don’t have to go through with this. I’m not even sure why I want to show you.”

He flicks my knee and then the box edge beside it. I give him what I imagine is a glower, which he receives with a virtuous squint. “OK, OK,” he says. “You want an accomplice. I’m game.”

I extend a leg and use my toe to coax the bag into the space between Ben and me. “I’ll grab both the manuscript and the pocket watch and see what happens. I’ve never tried to invoke a turning before. They just happen,” I say. “You can get out your notebook and whatever.”

“Oh, I was kind of kidding about taking notes,” he says.

“Well, I mean, you don’t have to do anything,” I say curtly.

“I could just watch,” he says. “Then when you come out of your trance, I can tell you what I saw.”

“It’s not a trance,” I mutter.

“Well, the turning.”

I tug at the drawstring at the mouth of the bag. “You’re sure you want me to try this?” I ask.

“Are you?”

“Someone should bear witness,” I say, not quite convincing even myself. “And it’s harmless, anyway. Like entering a dream world.”

“How long should I wait before I shake you or something?”

“Oh, you won’t need to do that,” I say. “I’ll come out of it. But you know, it might be a good idea to time it. Do you have a phone?”

He digs into his pocket and withdraws a thin gray device, which he then jabs at. “OK, stopwatch primed and ready to go.”

I take a long, deep breath and plunge both my arms into the mouth of the tote. “It usually happens with touch,” I say. “And listen, Ben, whatever happens, just let it run its course. Don’t freak out.”

With tentative, seeking fingers, I comb the smooth pouch until I come upon the cool metal of the pocket watch, which is resting in the cleft of the paper-clipped manuscript. I coax the watch into my curved fingers and brush the manuscript, almost like a cat pawing at a sliding door.

“OK,” I say with my head lowered slightly in preparation. “I’m not sure what you should look for, but it should happen pretty quickly.”

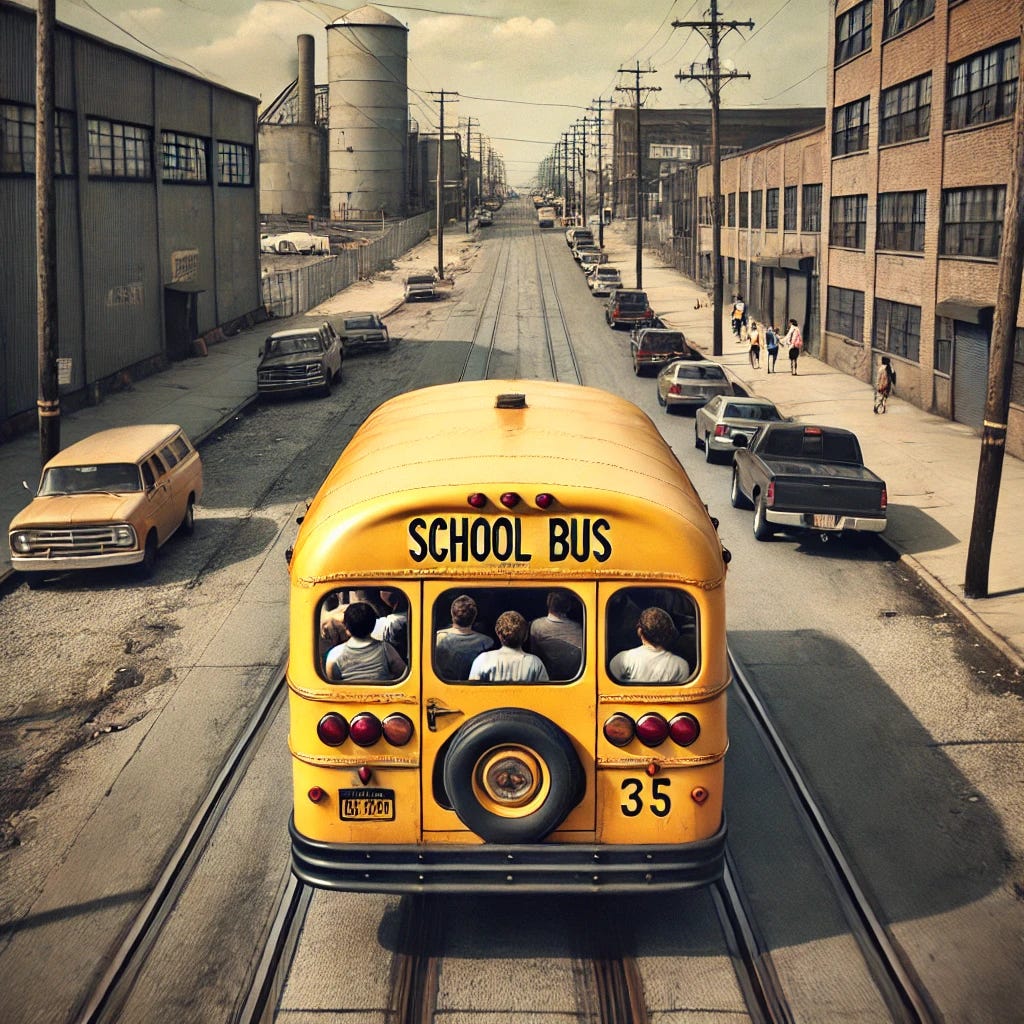

There is no reply. I lift my gaze from the lip of the bag and find that I am sitting on a bench seat upholstered with faded red vinyl. Beside me, there is a jagged gash in the material, from which a tuft of spongy padding peeks out. My hands are empty, but the bus is packed with teenagers wearing black tie attire. The full force of their raucous, clamorous chatter hits me all at once.

“Prom!” someone shouts from behind me. “It’s gonna be lit.”

The familiar, redolent aroma of bread wafts through the cabin. A young woman is sitting next to me with a croissant gripped gently in a napkin. Her face is full and florid beneath her thick auburn braid. She gestures at me with the tip of the pastry.

“Want a bite?”

I shake my head. “No, it’s OK.”

My wherewithal returns in recursive snatches of awareness. I have turned, obviously, but this is most certainly my memory, not my father’s. The young woman next to me has a familiar face. A classmate, maybe, but a bit player in my high school memories. While the bus careens along the canting downtown streets toward the Beacon Club, the harbourfront venue for North High School’s prom, my ruddy-faced bus-mate continues to munch on her croissant, dusting her frilly dress with unctuous pastry crunch.

We are on one of the cavalcade of buses chaperoned by a cadre of harried teachers in an effort to curb drunk driving. I am wearing my prom dress, an overly modest, royal blue gown that was, I remember, nearly a size too large. It appears I have pulled up the hem and tucked it under my seat to protect it from the amalgam of dried soda and miscellaneous grime on the textured bus floor.

We are near the front, and behind me, some of the boys have taken to dead-arming each other in a flamboyant pantomime of master and slave. One of the largest of the teens has buttressed himself against a bus window. His shirtsleeve is rolled up, revealing a reticulated network of bulging blue veins and inflamed skin. His jaw juts out as he heckles his fellow apes.

“That all you got, pussy?”

The chaperone, an elderly math teacher with an enormous, womanly rear, uses one of the leather loop straps hanging from the ceiling to hoist himself up.

“Hey, Braxton,” he says in his plodding drawl. “Come on now. No horseplay, OK?” He taps the vinyl backrest of the bench in front of him for emphasis.

Braxton stretches his thick neck toward the older man and offers a cocky grin. “OK, Mr. Bork,” he calls.

But the boys are incorrigible. As Mr. Bork gently plants himself back in his seat, the fleshy smack of a well-placed jab is heard, followed by a harsh whisper. “Jesus fuck, Brax!”

The bus judders over one of the dozens of potholes riddling the ill-kept quayside roads leading to the Beacon Club, which extends along a promenade at the far industrial end of the bay. I remember this ride, with its incongruous juxtaposition of bedlam in the bus cabin and the libidinal anticipation of the biggest of the formal dances.

And yet, the scene unfolding is uncanny, a few degrees askew. In my recollection, I sat not in the front of the bus, but somewhere in the congested middle, squeezed between Alex and Charlotte, with whom I attended the dance in a defiant dateless throuple. And outside the window, I do not see sprawling metal apparatuses that span Bonneville’s Factory District. We seem instead to be travelling along a country road corrugated with rows of dusty furrows and lined with birch trees bursting with frizzy yellow leaves.

We swing onto a driveway and trundle up to the front of a nondescript grey brick building with a freestanding, handprinted marquee that reads:

Sheepshead Bay Social Club and Meeting Hall

Sheepshead Bay. From my bench-side perch, I clamber onto my knees and turn around to survey the bus cabin once more. Now, scattered among the familiar animated figures are conspicuous anachronisms. One of the boys taking his turn pummelling Braxton has straight hair parted and pomaded to the side. He is wearing thick-rimmed plastic glasses and a bow tie with his tux. A young woman just behind me is sitting primly in the middle of an empty bench, her garish, cherry-red horn-rimmed glasses and atavistic updo, like Snow White’s, clangingly conspicuous amid the sea of layered Rachels and tricolour highlights. And there are others, other misfits, milling about, coalescing seamlessly with figures from my memories.

The bus grinds to a stop, and another of the chaperones, a thirty-something woman wearing a lilac skirt suit, cups her hands around her lips. “We’re here. Let’s be civil and respectful as we file into the building, shall we? No funny business.”

I disembark into the writhing, snaking herd of eager bodies and make my way to the large, open dancehall festooned with gaudy bursts of crepe paper flowers and streamers. A Buddy Holly lookalike trio is tuning their instruments quietly on the small stage overlooking the massive expanse of wooden dance floor, beyond which is a thick moat of burgundy carpet. A hand-painted banner is tacked to the rear wall. It reads:

Sheepshead Bay HS Promenade 1955

Braxton and his lackeys do not seem to notice that they have been transported more than sixty years backward in time to my father’s high school. They posture extravagantly with the young women in felt skirts, who twirl curled locks of hair. Some of my old classmates, nameless supporting characters of memory, chat blithely with a cluster of clean-cut boys in white tuxedoes.

Some of the minutiae, I realize with a start, has been cribbed from a movie whose name I cannot remember. I had expected to emerge in my father’s memory, but it is something else. Not quite his and not quite mine.

The throngs are becoming restive. A pod of prima donnas has begun to dance suggestively in the absence of music. Someone near the back tries to hurry things along with a shout just muffled by the crook of an elbow.

“Hey, what gives? Let’s go!”

The simpering guitarist salutes the crowd and then nods to the bassist and drummer in turn. He leans into the microphone.

“Check.”

“Just start already,” bellows a nasal voice just an arm’s length away from me. A chorus of snickers peals through the room in a wave.

The guitarist taps his feet and uses the neck of his instrument to give a downbeat. “OK, a one and a two and a—”

Forever young

I wanna be

Forever young.Everyone swarms the floor and begins to shuffle dance, their shoes gliding across the floor as though pucks on an air hockey table. The guitarist, pantomiming Chuck Berry, duckwalks across the stage, and the synth swells.

Do you really wanna live forever?

For my part, I remain on the carpet at the edge of the dance floor with the other wallflowers, agog at the unfolding pastiche. From somewhere out of immediate view, two cool hands grip my exposed arm, one at the wrist and the other at my elbow.

“Karina, we’re going to go, is that cool?”

Dazed, I swivel on a wobbly axis, and there, in vivid fidelity to memory, are Alex and Charlotte in matching sylvan headpieces. I reach up to pat my own thin silver headband, and my fingers caress the etchings in the metal leaves.

“Where are you going?” I ask.

Alex points to a sheepish, shabby duo, one sporting a pompadour and white tux and the other, Charlotte’s real-life prom date Dylan, adorned with hoop earrings, frosted tips, and a baggy, rumpled black button-down.

“Does that boy go to our school?” I ask, gesturing at the one who is not like the others.

Charlotte’s reproachful glower is made somehow more devastating by her Britney periwinkle eyeshadow. “Yeah, duh.”

She skips over to Dylan, the Millennial scenester, who takes her by the hand and leads her onto the dance floor. Wordlessly, Alex follows suit. Her time-travelling swain kisses her bent fingers like she is a countess, and then they, too, make their way onto the dance floor, where they promptly join a bunny hop line encircling a cluster of dancers doing the Macarena.

And then I am alone, just as I was all those years ago, when Alex and Charlotte, my “sisters in arms,” turned Quisling and went off with Dylan and Ian. In this funhouse recollection, Ian has been supplanted by a 1950s stock teen, but I am companionless, so the essence is intact.

I linger unnoticed on the burgundy carpet, which wraps around the dance floor like the moulding of a hideous picture frame, still mortified, even after all these years, and clinging to the remnants of a hairshirt. There are other isolatos milling about, the “freakshow menagerie,” gawky teenage boys with semi-tucked shirts and outcast young women whose crossed arms and defiant sneers just barely obscure the albatrosses they will carry in unseen places for the rest of time.

There are folding tables set up along the rear wall with gigantic aluminum platters of cookies and cut fruit and glass drink dispensers containing pale pink and cloudy liquids. I grab a small paper plate and pick out chunks of pineapple from a sea of green grapes. Handwritten signs with big block letters hang from thick twine from each of the glass vessels, in which slices of fruit are inexplicably suspended.

PINK FRUIT PUNCH

CRYSTAL PEPSI LEMONADE I begin to roam the dancehall, edging past small, chatty clusters of prom-goers and the odd chaperone dyad conferring in blithe tones. More and more teens are migrating from the florid hinterland to the syncytium of dancing bodies crowding the stage. The band is now playing Earth Angel, and the plodding, box-stepping couples sway with hands on shoulders and hips. A few deviants in the back are grinding pelvises against tailbones, and so the chaperones are dispatched to do God’s work.

A reticent hand taps my exposed shoulder. This time, it is not my friends, but a young time traveller, bedecked, as they all seem to be, in a grey suit with a dark bow tie.

“Excuse me, miss,” he says. His narrow eyes are a mossy green, and they are set wide on his tanned face, beneath which a nose like a sundial nob twitches nervously. “I saw you standing there, and I thought you might like to dance.”

I gape at him, aghast. His nervous little eyes dart from me to the dance floor and then back again. His paintbrush-thick pompadour slides forward with every shake of his head. “It’s OK if you say no,” he says. “No hard feelings. Honest.”

“No, it’s OK,” I say and, almost in spite of myself, I smile. “I would love to.”

My father’s umber face opens up into a canvas I know so well. He is beaming. “Wow, sure thing.” He lays a hand flat against his chest. “I’m Perry,” he says.

“Karina.”

A new song begins, and I turn toward the stage, where the guitarist has begun a nostalgic acoustic lead-in. A voice like gravel wrapped in velvet fills my ears.

“And I’d give up forever to touch you,

cause I know that you feel me somehow

You’re the closest to heaven that I’ll ever be,

and I don’t want to go home right now.”My father leans his head toward the dance floor. “I love this song,” he says and extends a hand toward me. “Will you dance with me, Karina?”

The words clink in my ears, evocations of past dances I have shared with my debonair dad throughout the years, at weddings and bat mitzvahs and the odd Italian restaurant. And maybe that is why I allow him to lead me to the dance floor with my clammy fingers held in his steady grip. Our memories are merging, it seems, coalescing in a clanging pastiche. I am a random prom girl, a one-time dance. He is the date I never had.

We find a small space next to Alex and her new beau. She leans her head on his narrow chest and smiles at me. The young man nods to my father, who greets him.

“Hi there, Clarence,” he says.

My father and I stand facing each other. His pupils are quite dilated, I notice, even in the coruscating light of the chintzy chandelier.

“When everything feels like the movies,

you bleed just to know you’re alive.”His hands hover timidly around my waist and I drape my wrists over his slight, boyish shoulders. We start to sway to John Rzeznik’s breathy allegro. I study the smooth, youthful lineaments of his face. He can scarcely look at me without blushing, but his compulsive politeness overrides his diffidence, and he allows himself only the occasional glance to his feet to make sure they’re following his instructions.

“I just want you to know who I am.”I edge closer and rest my cheek in the hollow of his neck, just as I used to as a little girl. He murmurs into my ear.

“Who did you come with tonight?”

“No one.”

He pauses for a moment. “Kind of hard to believe,” he says finally.

“I didn’t get an invitation. Nobody thought to ask me.”

“I would have.”

“I know,” I croak. “I know, Dad.”

He embraces me in a firm bearhug. I lift my head from his collarbone and find not a young promgoer staring back at me, but an old man. His wizened face is quiescent. His narrow eyes are closed. And there is a crimson crater in the centre of his umber scalp. I release him with an anguished cry, and he falls to the ground like a stone.

All at once, the lights in the dancehall extinguish. The music is swallowed in an upsurge of silence. I wail wordlessly into the abyss, daring it to flicker into a new view. And then, the scene shifts.

The odour that wafts into my nostrils is not fresh bread, but a potpourri of industrial deodorizer, stagnant urine, and the ghost of something more putrid. I am standing at one of the yellow-stained, low-lying porcelain sinks beneath a beveled, slightly distorted mirror with a cool S etched into the glass, sobbing into my hands.

“Hey, you OK?” someone asks from one of the stalls.

“Yeah,” I say, wiping my nose with my hand. I back away from the sink and out the swinging bathroom door. And sure enough, there is the familiar isolated hallway by North High’s graphics lab, with tattered cardstock fliers tacked to the locker-lined walls in a rainbow of grayscale clipart.

“I’m not doing this,” I say aloud. I pivot on my toes and sprint toward the exit door at the bottom of a wide stone staircase. I throw it open and lunge through, expecting to make a beeline through the staff parking lot. Instead, I barrel into a kid-sized school desk and knock it clatteringly on its side. A seated herd of pre-teens whips around in unison.

“Is everything all right back there,” says a plump woman with boy-short hair. She is diminutive and rotund, and she is wearing a denim overall skirt.

“Yes, Ms. Farmer,” I murmur instinctively and plaster myself against the rear wall.

The round little woman turns to the shrinking figure of a girl standing cross-footed at the front of the class with her clasped hands held at her navel. A tomato-red headband has been tasked with holding back a thicket of unruly curls. Her expression is one of suppressed terror.

“Go ahead, Karina,” says Ms. Farmer. “Tell the class what you did last night.”

“Well,” says ten-year-old me in a clipped falsetto. “We had a seder.”

“Is that how it’s pronounced?” asks Ms. Farmer. “Say-durr?”

She nods. “Seder.”

“And what is that, Karina?”

“Um, a seder is what you do at Passover. Everyone comes over to your house, and you all sit at a table to sing and eat and stuff.”

“What do you eat?” prods Ms. Farmer.

“Matzoh ball soup and gefilte fish and brisket.”

“Well, I think we all know what brisket is,” Ms. Farmer says.

“Oh, and matzoh brickle,” I add.

“For most of us, these are new words. Gefilte. Matzoh. Brickle. I’m going to run off some transparencies of Passover food for tomorrow so everyone can see. But why don’t you tell us a bit about your favourite food.”

In the rear of the classroom, I wince with a shuddering wave of preemptive shame.

“OK,” says my younger self. She begins to massage her knuckles with a forefinger and thumb. “It’s got to be matzoh brickle. Because it’s matzoh covered in chocolate and this, like, crunchy sweet caramel thing. And it’s—”

I watch my childhood avatar let down her guard and give herself to rhapsody. She smiles her gawky grin with its scattered overlarge permanent teeth crowding out the last of their antecedents.

“Oh, Ms. Farmer,” she gushes like an evangelical. “It’s so wonderful. It tastes like everything.”

And then Ms. Farmer guffaws. Seeing it again, replayed in vivid detail, I can almost taste this laugh, this little scoff, uttered innocently, but received like a hammer to the forehead.

“It’s a candy bar,” says Ms. Farmer. “It doesn’t taste like everything, Karina. It tastes like candy.”

The classroom erupts in laughter at my younger self’s exuberance, this temporary reprieve from pained, self-imposed reticence. Her elfin face flushes the colour of her headband and she stands there stuttering.

“I meant it…it’s like…oh…no…that’s not what I meant. I’m sorry…”

The children’s laughter seems to swell. I cannot bear to watch this Karina of twenty years past endure a shame so heavy, it wobbles her bony knees. I grope along the rear wall for the doorknob, which I twist with cranking force.

Through this portal is a kind of pregnant foreboding. There is light, but it is cast by an old lamp some distance away, freighted by an expanse of darkness that pushes against the feeble glow. From my vantage, I sense my nose is mere centimetres from a sliding door, cracked open just enough that I can glimpse a night table and a bed on which two figures are engaged in enthusiastic coitus. Slowly, I extend my arms akimbo, and my fingertips brush the stiff fabric of suspended clothing. Their wooden hangers jangle softly. I lean forward and glance the door, which gives just enough on its roller to confirm that I am in a closet.

The deviants copulating before me grunt and whisper. A female figure pushes her male lover supine and straddles him. “Straighten your legs,” she gasps. She runs a hand through her hair, whose silhouette I cannot quite make out in the lamp’s lazy corona.

I am at once mortified and indignant, and I try, vainly, to burrow into the clothing, but the mass of fabric is too heavy. I avert my eyes from what I fear is my younger playboy father and the mysterious redhead, whose rendezvous I glimpsed during the first turning.

Somewhere in the distance, there is a knock on a door. A thin, tentative voice calls out in supplication. “Mom? It happened again.”

The bodies cease their writhing. The woman leans back over the man’s shins. “I’ll be there in a few minutes,” she says, trying to stifle a panting breath.

“Can I come in?” The little interlocutor jiggles the locked doorknob with a quiet, tinny click.

“No, honey,” the woman says. She dismounts the man, who cannot help but let a disappointed hand fall to the mattress below, and slides to the foot of the bed. The lamp’s weak glow illuminates her naked, sweat-slick body. Her mess of gunmetal curls has been pushed back, revealing a widow’s peak. Her breasts hang limply above a crimped abdominal scar that crowds her navel. And her face bears an expression I have never seen. A peculiar mix of frustrated lust and maternal patience.

My father remains mercifully out of view, reclining in the cheap lamp’s expansive penumbra. “It’s that movie,” he whispers. “Why did I let her watch it?”

My mother rises, nude, and pulls on a pair of stupid fruit-print pyjama bottoms. “Oh, I don’t think it’s that,” she says. “Something happened at school. She doesn’t want to talk about it. Always so private.”

He scoots back to the headboard, an antsy shadow, and coos to her. “We can pick up where we left off when you come back.”

She chuckles to herself and tugs a U of B sweatshirt over her head. “We’ll see.”

I observe this unfolding scene in a kind of queasy torpor. I remember my younger self often waited outside my parents’ bedroom door, terrified or lonely, wondering why it was so often locked. This specific instance of outreach is opaque to my memory, but it now occurs to me that it is probably thematically linked with my fifth-grade humiliation. And of course, it is not my idea to crouch like a pervert in a fusty closet while my parents keep the proverbial spark alive, not my remembrance. Blinkered shock quickly gives way to righteous rage.

I leap from the closet onto the carpet, and my mother shudders in alarm. Somewhere behind her, my father rustles in the sheets. “What do you want from me?” I bellow. “Why this, of all things?”

At first, my mother’s eyes, the same carrot-in-swamp-water as mine, flash with an implacable defiance. Then, with what I can only assume is dawning recognition, her whole face softens “Karina, honey, you shouldn’t barge in without knocking.”

“No, not you. You don’t know anything.” I say and gesticulate at the figure behind her. “I’m talking to you. Why, Dad? I don’t want to be here. I don’t want this.”

“Don’t be mad at us, Karina,” says my father. His voice is low and gentle. “We’re just people who happened to have you.”

I bolt for the door and fling it open, almost colliding with my ten-year-old self, who nearly jumps out of her skin with fright. “I’m sorry,” I say to her, my voice cracking. She shrinks away with her hands clasped in front of her chest. I wheel toward the staircase and hurtle down the creaky wooden steps, where there is a magenta hair straightener hiding at the halfway point. Its heating plate catches my lead foot, and I am cast aloft.

I glide through the air as though I am swimming through a milkshake, prone and unhurried. The stairs pall under my spread-eagle shadow. Motes of dust hang like minuscule paper lanterns above the fissured, lacquered hardwood floor. I am on course to smash face-first into the dour multi-armed metal coatrack that stands like a sentinel before a generic support wall. If this were the world of solids, a trip to the hospital would be in my future. But I am somewhere else, betwixt and between, at the frontier of memory—mine, my fathers, and something altogether different.

My imminent impact could, I realize with a wave of rippling relief, bring me back to Ben and my parents’ empty house. But somehow I know it won’t. A nobby coatrack arm adorned with a beanie is now monster-sized in my vision. I open my mouth in a whimsical effort to swallow it and escape from this memory cavalcade.

My forehead strikes my open palms, and I give a little start, which rattles the shaky wooden cubicle in which I find I am now ensconced. Corded over-the-ear headphones sit lightly on the curves of my pinnas, their teardrop shape evidently not made for human ears. I scramble to comport myself. My elbows stick to the pages of a splayed textbook. I wrench them free and, sure enough, a single stiff gray hair sways in the binding like a cursed sapling.

I kick my chair out from the desk box and heave myself up. “Really?” I yell into the empty library alcove. “My first gray?”

I grab the textbook from the cubby and hurl it into one of the decorative plants at the edge of the desk cluster. Almost immediately, something viscous splatters against my cheek. I whip around, and I find I am now standing on a grassy median bisecting a busy street. A small legion of sign-waving activists rushes to surround me in a protective ring. Someone beside me shouts at a pickup truck idling at the curb. “Hey, come on now. That’s assault!”

I reach up to wipe a smear of marbled snot from my face with a familiar current of rage-tinged disgust. The hocker of the loogie sneers at me from beneath a mesh cap. His face is pocked and flinty, and he gesticulates at us with a middle finger so emphatic, it is almost hyperextended.

“Eat shit, hippies!” he yowls over the rev of his hemi, or whatever makes his departure sound like a rocket launch.

I reach down to pick up my sign, which I must have dropped. The din recedes in a whoosh, and as I try to rise, the apparent heaviness of the pole anchors me in a hunched squat. Something tells me that I should apply some force. I look down, and my hands grip a length of surgical steel, which I am pushing upward with shuddering exertion.

“Move the uterus anteriorly, Karina,” says the soft-spoken OB fellow, who offers gentle guidance from atop a metal stool. She reaches down to gingerly place an instrument on the patient’s abdomen, convex from insufflation. It teeters precariously, and on instinct, I reach up to grab it.

Beside me, a pear-shaped, bug-eyed nurse hectors me in a peremptory growl. “You do that again, missy—if you break the sterile field, I’ll slap you across the face, so help me God.”

I stare at her impassively, ever-aware of the watchers and evaluators. My resolve is heroic, and I say nothing. My hands tremble just slightly with the effort of keeping the t-bar steady.

“Oh, Peggy, I asked her to do that,” says the fellow. Beside her, the elderly chair of obstetrics chuckles, the old coward, with his rosy cheeks and John Lennon eyeglasses.

But the old nurse is implacable. “Yeah, well, if she does it again, I’ll smack her one.”

I am seething, filled with an animus so thick that I almost cannot speak. But unlike in the world of solids, this time I do. “Go for it, you cow,” I say, the words sticky in my mouth. “Let’s see what happens.”

Almost as a response to this blasphemy, this brazen infidelity to memory, the scene shifts once more, depriving me of a showdown I have playacted in the shower since my third year of medical school.

A small, square metal folding table comes into view, over which slumps a forlorn middle-aged couple. The woman has big, doleful brown eyes and beautiful wavy hair pushed behind her ears. She wears a drab day dress, whose wrinkles suggest alternations of long sitting spells and bursts of sweaty activity. The man, thin and pitted-cheeked, is wearing a bright white uniform. His gnomon nose twitches beneath small gray eyes, which are hooded with the accumulation of hardship.

“They don’t want me no more,” the man says to the woman. His accent is nonrhotic, slightly more street than Old Country. “It’s just business, he says. After ten years, it’s just business to toss me on my ass. You know how he did it? ‘Bergson, he says to me. What kind of name is that anyway?’”

The woman gestures toward the doorway of the kitchen. I turn to look at a curly-haired little boy crouched almost in the shadows.

“He’s listening,” she says.

The man’s face is impassive. He raises his voice to address the little interloper. “They’re all gonifs,” he says. “Remember that. You don’t trust no one.”

The scene shifts once more, and I am plopped onto a heavy padded chair beside a hospital bed, in which an elderly man is holding forth. A transparent nasal prong is clipped to the inside of his nostrils. The hiss of oxygen punctuates his bombastic boasting.

“I know it’s not PC to say this, so don’t go and complain. But I’m telling you, even now, an old piece of meat like me, I could get any woman I want. Even with the cancer. They can’t stay away.” He leans back in preparation for a deep, hacking cough, whose yield he deposits on the half-eaten food tray wedged under a lamp on his bedside table.

Before I can gather my bearings, he continues, recapitulating in mimetic detail a memory I have not rehearsed in years. It is the last conversation I had with an old man dying of end-stage prostate cancer, which he insisted on fighting with vitamins and his “natural immune system.” Today is the day he dies. And just hours before he goes into fulminant cardiac arrest, he delivered a soliloquy extolling his undying virility to me, a captive clerk.

“Have I told you who I am?” he asks, not really to me, but to alert anyone in the vicinity that they were in the presence of a bona fide VIP. “I’m the CEO of Endless Frontier. You heard of it?”

I shake my head. “Sorry, Mr. Tugwell.”

“Well, it’s one of the bigs.” A paroxysm of coughs seems to take him by surprise. He holds up a hand to signal me to wait, but when the fit does not abate, I jog to the door to hail a nurse. When I turn back, I discover I am now standing at the curled feet of my mother, who lies on the sagging couch in my parents’ living room, post-chemo, wan and contorted. Behind me, there is the rustling of socks on hardwood. A hollow, reedy voice calls from the kitchen.

“Mom, we have gunpowder—that’s a green tea. It could give you some energy. We also have Earl Grey and rooibos chai.”

My mother licks her chapped lips with a furrowed tongue and shades her eyes against the incandescence of the overhead light. “Green,” she croaks.

There is a crackling as the electric kettle is placed on the heating element. Before my mother notices me, I back into the hallway separating the kitchen from the living room. Through the arch-framed doorway, the Karina of memory is mouthing to herself in overlarge hospital scrubs, the billowing faded clown bottoms cinched below her ribcage with a frayed drawstring, and I cannot remember whether she had just arrived from the hospital or was preparing to head out. She stands on her tiptoes to draw a mug from the cupboard and peers inside before placing it on the counter. The teabag has been draped through the kettle’s D-shaped plastic handle, which is still my habit. She lip-synchs something with a scowl, which scrunches her dark eyebrows, bold and defiant beneath a tightly wound bun the texture and colour of steel wool.

I am drawn to her, this woman who looks like me, is me, was me. What is it like, I want to ask her, to be here now? With Mom sprawled on the couch like the mother in Munch’s painting, spectral, but still perfused with hot blood. Can I be you for just a few more dilated moments? I’ll stay here while you’re on service. I’ll care for Mom while you’re away. I have all the time in the world.

I am overcome with a desperate, seeking, erratic energy, which propels me into the kitchen. My double leaps with fright.

“Oh, my God!” she cheeps in a terrified treble.

“Shhh,” I say reflexively, waving my arms. “It’s me.”

She searches my face with the astonishment of a nonbeliever in the presence of a ghost.

“This is our memory,” I say breathlessly. “What is the date?”

“It’s—” she pauses to swallow. “November tenth.”

“You’re on pediatrics,” I say. “The rounding can take hours and hours. You have a protein bar in your pocket. I remember.”

She pats a thin, oblique rectangular bulge in a narrow hip pocket with tremulous fingers. From the other room, my mother caws peremptorily. “Karina, is that a video on your phone? It’s very loud.”

“We’re fine,” I call back.

“Who’s ‘we?’”

My double blinks at me like I am an irredeemable moron. “I mean I’m OK, Mom. Slip of the tongue.”

The hardwood crackles underfoot as my mother rises from the couch and begins to shuffle toward the kitchen. “You know what,” she sighs. “I need some saltines. This new platin turns my stomach inside out.”

My slightly younger avatar freezes in place. I turn toward the doorway to greet my moribund mother, who shambles into the kitchen with a fleece blanket wrapped around her shoulders like a fuzzy shawl.

Without moving her head, she glances first at me and then my petrified past self. “This fucking chemo,” she mutters, apparently too sapped to parse what must appear to be a mirage. “Do you think it’s helpful to walk a bit? They say I should rest, but I don’t know what feels worse, vegetating on the couch or creaking around like a goddamn zombie.”

It is a screwball scene, like something out of Sturges, but shot through with heartsickness. While my stupefied double looks on with her mannequin impotence, I lurch toward my infirm mother and squeeze her in a twiggy bearhug.

With hands like the sliding jaws of a vice grip, she squeezes the bones of my wrists together. I yelp. “No, mom. That hurts!”

I twist away from her lobster-like clutch, but it is not my enfeebled mother who then clips me in the neck with a knotty fist, but a much larger, thrashing, writhing man wearing a hospital gown.

“Bergson, try to hold him down,” gasps a man with a sing-song cadence. “Oh, my God—Mr. Cramby, can you settle? OK? We know you’re uncomfortable, hon, but we’re trying to help you.”

The scene quickly comes into clamorous view. It is a maelstrom. A very stout, red-faced nurse is wedged beside me, her hands braced against the patient’s writhing hips. My thighs push into the cold, nobby metal frame of a hospital bed. A middle-aged man is turned on his side, his bare legs bucking like a spooked horse’s, his face pressed into the starched white sheets of the mattress. He groans and grunts, and his shrivelled penis peeks out from his untied gown every now and then like a pig-in-a-blanket. At the headboard is Reggie, the resident I worked with during my general surgery rotation in my fourth year of medical school. His fitted black scrubs are splattered with a cloudy substance of indeterminate colour.

“Oh, God,” I murmur. A current of nausea reaches into the depths of my abdomen and climbs into my throat. A draught of the most unholy smell I have ever smelled wafts into my nostrils, a sour, puckering amalgam of waste and warning.

Reggie motions to me with his chin. “Karina, hold him down—yes, any way you can, just do it.” He turns to the patient, who thrashes against my reluctant hands and the stalwart nurse’s boa constrictor grip. “Mr. Cramby, we need to decompress your stomach, OK? The tube has to go in through your nose. Do you understand?”

The nurse cranes her neck back and calls to another nurse in the hallway. “We need hands!”

“And get me a five and two,” shouts Reggie. “Stat!”

He nods at the nurse. “No risperidone for the aggression?”

She shifts her weight to dodge a kick. “No, the wife doesn’t want him on meds, but they used some Haldol last night,” she says. “It took a full em gee to get him to settle. Then they noticed his belly.”

“SBO on a picture of advanced frontotemporal dementia,” Reggie explains to me in an urgent staccato. “He’s not himself.”

The patient shudders with a retch, which stills his body for just a moment.

“Oh, shit,” says Reggie. “Guys, move back.”

But I am too late. The man undulates with a purgative paroxysm of pain. A fountain of tawny, chunky fluid splatters my scrubs. And then I, too, retch.

We are facing each other now, the patient and me. The nurse and Reggie have taken cover behind the speckled curtain bifurcating the room.

“I’m sorry,” the man splutters through bits of feculent vomit. His narrow, wide-set eyes flash brilliantly green in the glare of the overhead light.

The stink is so thick that it chokes the breath from my throat. “You fucker,” I rasp. “Why are you doing this to me?” I pounce on him like a lion and mash my fists into his lined umber face, which is frozen in a grotesque mask of injured innocence.

“What do you want from me?” I shriek. “Dredging up these memories? For what, huh? Feculent vomit isn’t bad enough. I have to relive it here, with that goddamned disgusting smell, but it’s your face I see.”

He says nothing. His idiot mossy eyes are glassy and staring past me, mouth slack and daubed with excreta.

I leap off the bed and bolt into the darkened hospital corridor. It is nearly empty, evacuated of bustling nurses mumbling to themselves and the perennially downcast janitor piloting an industrial floor buffer. The scuffed white walls recede halfway down, where the corridor melts into abyssal darkness. A mobile computer station drifts into my vicinity, and I kick it with all my might, sending it careening into oblivion.

“Let me out!” I scream.

But of course, there is no reply. Just a yawning maw of infuriating darkness, into which I barrel at a full sprint. I am crazed, desperate, discombobulated. And I am trapped. The usual safety valves seem to be clogged in this purgatory, and so I must endure an endless cavalcade of baffling memories, some mine, some spliced with my father’s, but all slightly tilted, like the reflections of a cracked funhouse mirror.

The darkness gives way to a semicircular nursing pod, an oasis in a desert of institutional drabness, at which a woman is hunt-and-pecking on a computer whose contours become more pronounced as I near. She looks to be in very early middle age, rotund, mouth pursed in a sassy crescent. Her ponytail is cinched so tight against the back of her skull that her penciled eyebrows arch in perpetual surprise. She hails me as I approach.

“Hey, are you the resident?” she asks loudly. Before I can respond, she barks an order at me. “I need you to check on three. Mom is asking to see the on-call.”

In my periphery, bright, colourful geometric shapes and chintzy, Seuss-esque animal prints seem to pulse. I survey my new surrounds, and the scene has once again shifted. I am in the pediatrics ward of St. Dympha Hospital.

“I just got here,” I say.

“That’s not my problem,” she retorts.

A tinny, drawling post-menopausal voice sounds from overhead. “Dr. Bergson, please come to the nurse’s station. Dr. Bergson, if you’re on unit, come to the nursing station.”

“See?” says my detractor. She points to the large, crescent-shaped desk, with a sleek, raised vinyl countertop.

Sure enough, true to my memory, there is a young male nurse reclining with his feet on the desk, mere millimetres from a quarter-full cup of cloudy coffee.

He motions to the landline phone with the tip of a lackadaisical teal foam clog. “It’s Dr. Balastrada.”

I pick up the receiver, and Dr. Balastrada’s fluid, imperious, girlish soprano flows forth. “Karina, it’s Tiffany Balastrada. OK, a few things to know. I live, oh, forty-five minutes away, and I have two girls under five. So as you can imagine, life is very busy for me, and I’m always pulled in literally eighteen different directions. Honestly, I’m counting on you to run things tonight. You can call, of course—and I want you to know you’re always supported as a learner. But keep in mind that if I need to come down, it really will be, like, at least forty-five minutes. Maybe think of me as here, but not here, not physically here. It’s a good learning opportunity. We’ll review in the morning, so if anything comes up you want to debrief about, we can talk about it at seven am.”

In perfect fidelity to memory, she means to leave me alone on the twenty-bed pediatrics ward, from which, if needed, I can also provide overnight coverage to the small postpartum ward downstairs. It was my third rotation, and I was cowed by Balastrada’s diktat, which at the time seemed like an occasion to which I should rise. I did, indeed, allow the attending-cum-mother-on-call to sleep. No one died. I hovered around the nursing station, coiled like a novelty snake-in-a-can, ready to spring into action. Morning came, and there was nary a thank you from Balastrada, who instead seemed put out by the long, neat notes I left in the charts of the patients I visited in a cold sweat overnight.

But now, I am unhinged, liberated, righteously indignant. “A good learning opportunity for me,” I hum into the receiver. “And an easy three grand for you.”

Her honeyed voice takes on a gravelly timbre. “Excuse me?”

“And a full night’s sleep, too. Med ed’s a great gig, isn’t it?”

“Karina, this is very unprofessional behaviour.”

“There’s so much I’ve always wanted to say to you,” I say, gearing up, finally, for the consummation of a shower-tile confrontation fantasy. “You know we’re the same age, don’t you?”

“That’s not relevant,” she crackles.

“As far as you’re concerned, you’ve earned it. Medicine took your youth, so you’re going to make up for lost time.”

In my bathroom pantomimes, my opponents are usually stunned by my invective, but this Dr. Balastrada is clairvoyant and suddenly barbarous. “This is really pathetic,” she says. “Why don’t you just go home right now? What’s stopping you? You don’t have kids. No parents to disappoint anymore. You could go back to watercolours and poetry, twice-weekly pilates classes at the Y. Sure, from a life perspective, you’d have your lips wrapped around the barrel, but at least you’d be free.”

“Maybe I should have,” I say. “That night, when I was here before. I didn’t realize what you were, leaning in by day and stepping on the heads of the women under you in the dark of night. But bravo, Tiffany. You’ve earned it. You paid your dues, and now you’re a supermom. We’ll pay your mortgage while you sleep.”

Our connection is becoming increasingly staticky. “It’s scorched earth out there, Karina. And let’s be honest, you keep slipping into potholes along the yellow brick road. We’ve packed you a shit sandwich, girlfriend. All you have to do is eat a little bit each day and pretend you like it.”

I scoff into the phone. “All I have to do is not become you.”

“I know you don’t mean it, this acting out. You’re just a little tired. A bit burnt out. Do some box breathing in the callroom. And lucky you, tomorrow is self-care day. Treat yourself post-call. Attagirl.”

She is getting the better of me. It is a burlesque, no question, slippery words spilling from a slant mouth. But she is capturing the essence of it all, the tacit and assumed. My pugnacious facade gives way to sweat-slick dread. “There’s no way out, is there, Balastrada?”

The line croaks with what sounds like a robot burp. “Doctor Balastrada. And no, there’s no way out. Not just for you, but for everyone. Could be a lot worse. How quickly you forget. Why don’t you go see the little bronchiolitis girl in three? Her mom’s a real entitled bitch, and you’ve got no backup here, but I think it would be good for you to lie down and let her stomp on your neck. What do you say?”

“I don’t have a choice, do I?”

“Not just that, but deep down, in the little hiding places of your soul, you know you’re nothing. A grovelling, snivelling, worthless zero. Don’t forget that, Karina. You’re the little piggy who built her house out of straw. Stop feeling sorry for yourself and be grateful for this bit of cosmic good fortune. You were supposed to scrape the very bottom of the barrel. Who says there’s no such thing as luck?”

A mewling child’s cry pierces through the static. “I’ve got to go,” she says. “Call if you need. But don’t.”

I hand the receiver to the male nurse, who is now playing a chunky, vintage gray Gameboy, and he tosses it into the wastebasket underneath his seat.

Dazed, I wander down the desolate hallway to the patient’s room, my ears ringing in a textured tritone. The door is oaken and heavy. For some reason, a dull, smudged mezuzah is lofted near the hinge. I push through and emerge in a small, cooly lighted chapel with low-pile carpet and a slightly raised platform, behind which is an ornate cabinet panelled with a stained glass tree.

At the edge of the platform, a group of preteen boys and girls sits cross-legged before an older man wearing a yarmulke and a close-cropped, bristly white beard. He is perched on the lip of the bimah, and his long legs bunch up nearly to his chin. He speaks to the children in the mid-century cadence of Sheepshead Bay, and they sit, rapt, little white tassels of tzitzit spilling from pants, unpinned yarmulkes askew, dresses rumpled under wiggly legs. I sit in one of the folding chairs at the back of the room. As usual, no one seems to notice me.

“And God brought his children out of Egypt. And they wandered in the desert for forty years. Can you imagine? Where were they going? They knew nothing. But went they did. To the promised land.”

One of the children, a boy whose kinky black waves buoy a knitted yarmulke that begs for a clip, raises his hand.

“Yes, Pinchas?”

The boy shifts on his seat, revealing small, seeking eyes and a nose like a little sundial. “Weren’t they scared, Rabbi? All alone in the middle of the sand. It’s kind of a bum deal.”

The rabbi leans forward, his forearms resting on his jutting knees, and nods with downturned lips. “A bum deal? You could say. But also a gift. The old rabbis tell us the world is a narrow bridge. Even in the desert all those forty years, the world was a narrow bridge, and the Children of Israel had no choice but to walk from here to there. To go anywhere, God is showing us, first you have to leave. Not just your bread and your things, but everything you know. Your home, your city, the life you had in that familiar place. And once you’re on your journey to somewhere new, with your mind open wide as can be, then you can start to look for what you’re looking for. This is what is most important, why we talk so much about the time we were slaves in Egypt. God sent us on our way. So that we could go somewhere new.”

He allows this bit of homily to hang in the air for a long moment. The children are staring up at him, mouths parted, at once confused and captivated.

“This was more than five thousand years ago. Can you believe it? They left footprints in the sand, and maybe you might say they left footprints in our memories, all these years later, so many miles from the Land of Israel. Would you agree they left something in us, maybe? A little sand in our hair? A trace of the wilderness in all of us.”

The boy, Pinchas, turns to face me. His mossy little eyes are soft and bright. “You see, Karina, the past leans over the present.”

I am not startled at his address. In a sense, I had expected it, this changeling spectre who haunts me in his memory labyrinth. The other children turn toward me, a sea of coarse, curly hair and coloured eyes, and the old rabbi motions for me to join them.

“Why don’t you sit with us?” he says.

I untwist my legs and approach the group, which parts like the Red Sea so that I, too, can sit crosslegged on the low-pile carpet. I settle next to my father, who scoots over with muted magnanimity, even though he is himself quite bantam and I don’t take up much space.

“So,” the rabbi says. “What gives?”

He has a kind, placid face, wizened and weatherbeaten, like an old alpinist’s. “You tell me,” I say, and then I remember to add the honorific. “Rabbi.”

His crowfeet ripple outward, creasing the contiguous skin like sand seams in a desert. “God brought his children out of Egypt,” he says. “And we carry that memory with us. The wilderness.”

“The wilderness,” I say. “All I want is to go home.”

“What is your story?”

“I am literally lost in memory.”

“Are you an angel, then? Malach? She who is sent on an errand, or maybe with a message?”

“Wouldn’t I know if I were an angel?”

The rabbi shrugs. “There is no such requirement. Only an errand or some such. Or maybe someone else has a message for you.”

I turn to my boyish father, who has his elbows propped on his bare knees and his head cradled in his hands, scrunch-faced. “Let’s ask him,” I say, the last word bristling with charge. “What gives, Dad?”

The boy’s mossy little eyes widen. “Dad? You can’t be a dad at twelve!”

I ball my fists, more exasperated than angry. “But this is your memory. I’m like some kind of—I don’t know, some horrible cursed visitor. You’re…” My voice falters. “Look, you’re not always going to be here.”

His little prepubescent nose, not quite a robust sundial nob yet, twitches nervously. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he mutters.

The rest of the kids are deathly silent, though in their smooth, scrubbed faces are the many varied terrains of disquietude and bewilderment.

“What a place to have such a discussion,” says the rabbi, spreading his lined hands. “For how can we become bar and bat mitzvahs without asking where we come from and where we are going? This is what we are always talking about. Out from Egypt we went. Out from Egypt we are always going.”

“So I’m stuck,” I say. “That’s what you’re telling me. Everything is cyclical. My dad and I are connected. There’s no way out.”

“Blessed may you be in your coming in and blessed may you be in your going out,” the rabbi says with what I read as glib piety. “I do not mean this to be a mystery. God is in the comings and goings.”

These sententious pronouncements fill me with a righteous kind of rage. “Stop talking like that,” I say. “Just stop. It isn’t God in the gaps. It’s nothing. You’re reflecting my own terror back to me. I can’t leave this place. And this isn’t even my memory. It’s my dead father’s.” I thrust a trembling finger at the boy he once was. “Why?”

The rabbi shrugs, unfazed by my outburst. “I am not so worried about being lost. There is something tied to each of us. A thread, maybe, something a spider might spin, very long. Its little loops catch on everything, and time does not snip it. But why are you here? I don’t know. And yet, what a gift, eh? To wander through memory, yours and others. Like Jacob and his ladder, but it isn’t a dream.”

Tears well up, blearing my vision until I blink it clean once more. “Isn’t there supposed to be a lesson here? Some moral? You’re my sphinx, aren’t you?” I lean back on trembling hands, my crossed legs providing ballast. “And these little fuckers are the Greek chorus.”

The rabbi chuckles and clicks his tongue. “Such language,” he says. “You want I should give you wise counsel, like Rabbi Tarfon or Maimonides or the Baal Shem Tov?”

“Let me go,” I plead. “Give me a riddle. I’ll run the gauntlet. I’ll learn the lessons and live virtuously and, look, enough is enough, all right?”

“Enough,” the rabbi intones with rumbling gravitas. “The Jews have often said the same thing to God. Enough, they cry. Enough suffering. Enough pogroms. Enough uncertainty. And only once in all of our human history have we heard anything from God. The old rabbis, they argued amongst themselves—this was a very long time ago—they argued about this very thing. They debated and debated, and finally they settled on something. God spoke only once, they decided. It was one sound, the first letter of the first commandment. The aleph—the Immense Aleph, they call it, Karina, for God’s voice was so thunderous and beyond beyond beyond that it filled everything everywhere with God’s splendour. It was terrifying and awe-inspiring, this experience of Ein Sof, the One. Everything that comes after that, all the writings and arguments and speculations and doubts, it’s interpretation. That is what is meant when we say Jews are people of the book. God continues to speak to us through our insights, through our togetherness, through our talking and laughing and shouting and demanding and negotiating and meaning-making. God speaks to us through our journeys, too, the lives we live. They, too, are expressions of God. We are expressions of God.”

I stare into his weatherbeaten face, with its tight, lined skin, like a Semitic Samuel Beckett. He smiles and nods toward my young father, who is watching the scene with lips parted and nose twitching. “The past leans over the present,” I repeat. “God is in the gaps. Do you have more to say?”

He shakes his head. “I don’t even know what it means. I just thought to say it.”

“Will you let me go, Dad?” I ask.

He looks up at the rabbi in obvious distress. “Maybe you should go get some fresh air,” the older man says. “It’s beautiful outside. I was just out for a jog.”

I rise from my spot, tingle-footed, and the children again part to let me through. Up the carpeted stairs I go. I can feel the charged gazes of the rabbi and his Hebrew school flock on my back like a sun itch. I push open the heavy door and stride back into a hospital corridor.

It is too brightly lighted, clogged with wheel-fitted trays and stands and frenetic, hurrying bodies. Exhausted and somewhat chastened by my back-to-back encounters with Balastrada and the rabbi guru, reduced to a spanked and bewildered child, I make my way through the seemingly endless tunnelling corridor as though on a conveyor belt, not submissive, but resigned, maybe, open to the abyss. I need to find a quiet milieu, a place to still my mind and pitch my lasso.

I stride through a busy hallway junction, where a gaggle of harried nurses nearly collides with an older physician wearing a lab coat and twisting her watch on her wrist. I hug the wall to avoid the welter and when I can, I turn down a smaller auxiliary hallway. A petite, elfin blonde woman wearing cat-eye glasses is charting on a mobile computer station. She looks up and smiles at me in greeting.

“Karina, what good luck you’re here,” she says.

“Dr. Witnik,” I say with dawning recognition. “Nice to see you.”

She scrunches her chipmunk nose as she peers up into the screen, lips parted just enough to show the bleached bottoms of her incisors. “I’ve got a bit of a head-scratcher,” she says. “Can I run it by you?”

Dr. Witnik was a supervisor of mine for just one day when I was a resident on the labour and delivery service last year. Sprightly and motormouthed, she bumbled along. At the time, I marvelled at the sheer volume of questions she lobbed at me. Usually, attending doctors pose questions to intimidate, to assert superiority, but not Dr. Witnik. I had the sense she genuinely didn’t know.

“Yeah, sure thing, Dr. Witnik,” I reply distantly.

“Maybe you could go see this baby and let me know what you think,” she says. “I keep calling his name, but he isn’t responding.”

I stare at her for a moment, stunned at this spectacular neural misfire. She locks the screen with a limp-wristed flourish and hooks the crook of my elbow in her other hand, small and spindly.

“The newborn isn’t responding to his name?”

“I know, right?” she says. She leads me the few steps to a baby blue door with a small window just above both of our lines of sight. She hip checks the door, which swings open, and gives me a little shove through.

A phalanx of nurses, doctors, and lookie-loos dressed in surgical gowns and hats crowd a surgical table, on which a procedure is evidently underway. Nobody turns to look at me, and so I rim the perimeter, outside the sterile field, perhaps out of fear-honed habit, and keep my hands up near my chest. This is a silly reflex, I realize, so I let them drop.

A young man is standing beside me furiously scrolling on his phone. He, too, wears a surgical cap and gown, but his hands are conspicuously ungloved. His tanned, hairless arms snake out of his scrub shirt, and his large blue eyes are the only feature clearly visible above his mask. I scour my memory banks, but without an unobstructed view of his face, I cannot seem to place him.

“What are you doing?” I whisper to him.

“Can’t talk,” he rasps back. “They sprang it on me. I’ve never done a craniotomy. For fuck’s sake, this is only month two.”

It dawns on me that he’s watching a video on his phone. Little bursts of lumen dance along the edges of the screen, which I can just glimpse from beside him.

“You’re learning how to do it from an Internet video?”

He glares at me sidelong. “How else am I going to learn?”

“Seems like a big risk,” I say.

“Well, whatever,” he replies.

We are silent for a moment, and then I feel emboldened. “Why don’t you show me?”

“What, you’re going to do it?”

“No, I’m curious.”

He cranes his neck to survey the room. The scrub nurse has returned to her shiny metal tray arranged with objects meticulously organized according to some arcane system. A veritable pod of gowned figures still hovers around the table, obscuring it from view. The surgical resident shrugs and passes the phone to me.

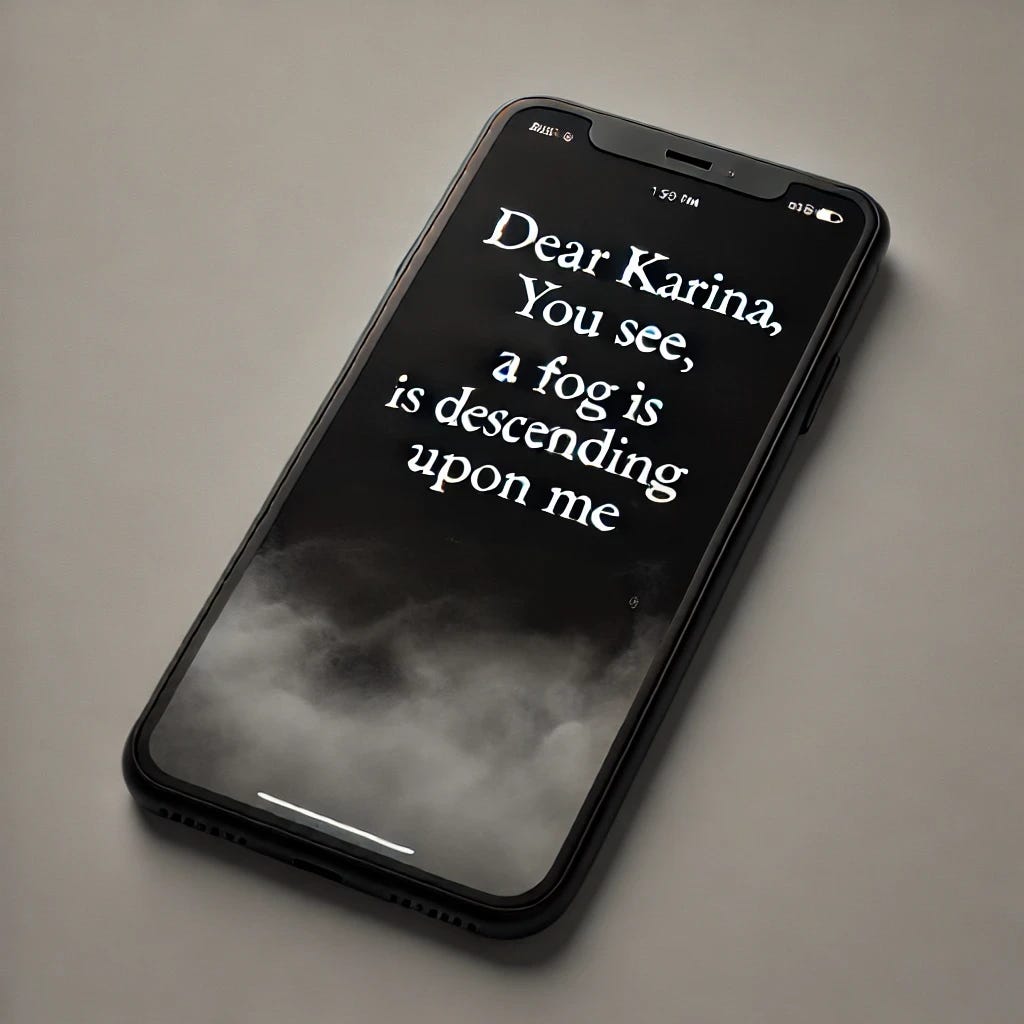

But there is no lurching, dilettante instructional video of brain surgery being performed in some benighted, far-flung locale. The screen is inky black. Blocky typeset text crawls across the screen like the opening sequence of a movie, but garbled and jolting. Before I bolt once more, back into the abyss, I read it in its entirety.

Dear Karina,

You see, a fog is descending upon me

the past leans over the present, and its emissaries, memories, stretch across the great cosmic expanse

Have I lost you?

Everything is always becoming, Karina

- we hold the infinite!

traces time leaves in our neural architecture

histories of ourselves, compendiums of memories

free only so long as we can ask ourselves what to do with this time.

Time is everything, Karina

Soon, your place will be thick with the material of memory

Festina Lente, Karina.

Make haste slowly.

*Note: The illustrations accompanying this story were generated using AI technology. I’ve left them as a sort of cyber-hairshirt. Please read my repentant anti-AI mea culpa and, if you can, forgive me.