Welcome back to Only by the Grace of the Wind, a slightly surreal novel presented in twelve serial chapter instalments released every Monday morning.

In an effort to expand my readership, this chapter will remain free to read. Please don’t forget to like, comment, and share!

Feeling lost? You can get your bearings by visiting the Table of Contents

For as long as I can remember, I have had a recurring dream. It is always the final scene in the night’s anamnestic drama, revealed like a rainbow after a summer storm. It sticks with me, this paint-spattered air castle, glittering with the residue of saudade, like the rest of the treasured memories that never again can be.

I had an iteration of this dream the night before each of my parents’ deaths. We could call it synchronicity. That seems innocent enough. But a part of me believes there was something more to it, something numinous, maybe, a salutary brush with the sublime before a tidal wave of worldly grief.

It always begins the same way. A draught of wind catches me under my arms, and the unmistakable tug of aerodynamic lift draws me onto my tippy-toes. I pick up my pace, tasting the air with hands like paddles, and sure enough, I take off, ascending first to the middle boughs of a nearby tree and then high into the sky. The ecstasy of freedom comes immediately, but I have to assure myself that this inaugural launch is not a fluke. So I glide back to Earth, risking permanent grounding, and try again. Once more, I hurtle down an ad hoc runway somewhere in dreamland with my arms outstretched. Gentle wafting currents catch me and lift me up, up, up, past the billboards and generic buildings and into the glorious, wide-open sky.

Sometimes, in these dreams, I have somewhere to go, some obscure errand to run, but often I just soar along the cloudline, observing my world from a bird’s vantage. It is always a terra incognita, unknown but also uncannily familiar. The chunky terrain, equal parts metropolitan and Arcadian, spills forth in an endless expanse, curved just so at the horizon line. This is the perspective of God descending, or maybe just a volant voyeur, peering down at the land-bound, blissfully untethered and exulting in her cosmic good fortune.

I am always disappointed when I awaken, freighted by gravity and mundane expectations. The horizon looks very different from below. But it turns out the awakening is itself a blessing, for a dream-reel unending is something else entirely. An inexorable journey without a destination. Could there really be such a thing?

This is no mere luftmensch’s rumination. Like a hapless actor in a cursed one-woman show, I am enacting a story without an end. The Israelites did eventually make their way out of the desert, didn’t they? A bit sandy and wind-burned, maybe, but hale enough to hunker down somewhere in the ancient Levant, preparing for a few thousand more years of ineluctable misery. So says the rabbi from a few memories past.

For my part, I am still here in this liminal, inscrutable place, somewhere between lives lived and remembered. The memory cascade continues to pour forth, creating little riptide moments in which I get caught in tilting recollection, only to be cast adrift once again. And yet, in the past few acts of this never-ending play, there has been a shift, barely perceptible, possibly illusory. Something is changing.

Presently, I seem to be back in the small, familiar ramshackle kitchen, where my grandparents had admonished my very young father to beware the gonif goys in New York, the mid-century American Pale of Settlement. I lean over the stove with my grandmother, who does not seem to notice me. She is sturdy, but not stout, with a long, thin face and Roman nose, a crypto-cousin of Virginia Woolf. Her gorgeous sandy hair is tied back with a colourful berrette. not a grey in sight. Little kreplach float in the tin pot’s cloudy broth. She prods them with a ladle.

My grandfather is again home. He is older now, with quite a bit of salt in his stubble and high peaks in his close-cropped hair, which stands up in corrugated waves. He watches my grandma with a stern expression pulling his olive skin tight across his high cheekbones. They sit together in silence in the soup-scented kitchen, with the soft burble of the simmering broth. I imagine this is their habit.

In the distance, a door clicks shut, and my father lopes in almost sheepishly. His lip is split like a blistered tomato. His button-down shirt has been torn at the collar, where there are deep crimson and purple bruises crisscrossing his neck, shoulders, and chest. He is out of breath and blinking quickly.

My grandfather spots him first. He rushes to the doorway and takes my father’s face in his hardscrabble hands.

“What have they done?” he barks, his accent now more shtetl than street. “Look at you. Beaten to a pulp.”

My father is abashed. He averts his mossy little eyes, an inheritance from the man before him, and thin runnels of tears run down his face, collecting blood from dried brown streaks.

“I’m OK, Dad,” he says softly. With trembling hands, he reaches up to his father’s to try, in vain, to break his paternal clasp. By this time, my grandmother has caught sight of her battered eldest. She gasps and emits a muted wail.

“Oh, God,” she moans. “Perry, no. Who should I telephone? Doctor Zalenger?”

She, too, rushes over to my father, tugging softly at his riven shirt. He tries to mollify her by brushing her shoulder with his fingers. “I’m OK, Ma. Really.”

My grandfather steps back to observe him. He bites his top lip and grunts. “Who did this to you?”

“There was a march. I wanted to support them.”

“Who, the schvartzers?”

My father frowns. “Don’t call them that.”

“What I should call them?”

“Negroes.”

“It was cops what did this to you?”

My father winces as his mother prods his lip with an outstretched finger. “Ow, Ma. Easy.” He nods to my grandfather. “Me and some of the neighbourhood guys thought if we were there, it would help.”

“You are a good man,” she says, cupping his chin gently in her palm.

My grandfather’s lips dip down into an arch. His own mossy little eyes are so squinted as to be slits. “A brave man,” he agrees solemnly. “Like the Bundists in Kyiv.” He thrusts his fist into the air. “Daloy poltizei!”

My father frowns as he tries to puzzle out the Yiddish watchword. “Police?”

“No more police.” The older man cuffs his son on the neck, which elicits a wince. “You are our son,” he says fiercely.

My grandmother rushes over to the small metal folding table and pulls out a chair for my father, onto which he lowers himself gingerly. My grandfather grabs a small wooden stool from the narrow hallway outside the kitchen and sets it down before my father. He then draws three glasses of water from the tap and sets them on the table.

They sit together, these relics, each of their heads held aloft on proud necks.

“Where’s Dee?” asks my dad.

“Work,” says my grandfather. “She’ll walk home with Leah.”

“It’s rough out there,” my father says. “We were just marching, and they blindsided us with their clubs. Some of them weren’t even cops. They were just guys.”

My grandmother clicks her tongue. “Rotseyekhs. Disgusting monkeys. Attacking their neighbours on the street.”

“You are our son,” repeats my grandfather. “The apple does not roll far.”

“Uncle Meyer says you guys were real revolutionaries,” my father says. “Back in the old country.”

Both my grandparents stiffen at my father’s cavalier invocation. “The whole story he told you?”

My father pushes his fingers into his masseter muscle and opens his mouth carefully. “No, he said we’d talk about it later.”

“Well, then I will tell you now,” says my grandmother in a stentorian voice. She looks down her regal nose at my grandfather, who shrugs and offers an impassive, purse-lipped nod. “For us, they came. Not once, but too many times to count. We had to fight. They would kill us and think not one thought. So we took up with the Bund.”

My grandfather leans back in his chair, balancing on the back legs, his shoulders just kissing the kitchen wall. “This was before we came to America. On a big ship, stinking to the sky, my God.”

My father shakes his head with more than a whiff of irony. “The land of milk and honey.”

My grandfather scoffs, but his lips are curved into a wry smile. “Land of gonifs,” he says. “Your mother, she threw a bomb. It was night, but even a bomb in the night leaves behind something. Meyer, the mensch, he put us on a ship. Here we come with two dimes in our pockets. The next year, he comes.”

My grandmother is beaming at my father, whose mouth is held in a slack O, as though someone just knocked a cigar from his lips. “You threw a bomb?”

She nods. “That was the last thing I threw.”

“Jeez, ma,” says my father. “I had no idea.”

My grandfather flicks his shoulder lightly. “It was for the others. Not for fun.”

“Oh, I know, Dad.”

“I am proud,” my grandmother says. “Of course I am proud. Would you know I was so brave, to do such a thing?”

All this time, I have stood still, like a terra cotta soldier, in the corner of the kitchen, watching, listening. I might as well be furniture. While my grandmother waxes revolutionary about her kick-ass past, something is shifting and swirling behind me. At first, it is subtle, quiet, like a weak magnet’s repellant force. Then the air changes and a sound rings out, a creaking tree in an alpine forest.

I turn from the kitchen discussion. There is now an expanse of hardwood floor stretching toward a new horizon, where a saggy, bow-framed couch creaks under the weight of a figure in repose. The woody groan is a door opening. A slumped, droop-shouldered figure limps in with the help of a larger silhouette. The man on the couch leaps up and rushes to the small, hobbled woman, whom he takes in a gentle embrace. The silhouette offers a few indecipherable words to the smaller man and pats his wounded comrade on her fuzzy head before exiting the scene.

I cast one final glance back at the lively conversation unfolding in a Gotham kitchen sometime in the 1950s. “You want I should get some ice from the box?” my grandmother asks. She gestures toward the corner of the kitchen, where I am lurking, but my father restrains her with a palm laid on her forearm. “I think I’ll sleep this one off, Ma.”

He totters out of the kitchen. As though pulled along by an invisible thread, I exit the little apartment and drift along a long corridor of hardwood stretching along a parabolic plane to the far opposite horizon. My footfalls evoke the grasshopper crackle I associate with the living room in my parents’ house. There, my father and a slightly younger Karina are lowering themselves onto the saggy-cushioned couch like boxers after ten rounds. My younger self appears dazed. Her lids are leaded. Someone has gathered her hair into a side bunch and secured it with a rubber band. A hematoma is visible on her forehead, raised like a purple egg, and as I approach, I can see the greenish smear of a grass stain running along the seam of her jeans.

I walk right into the centre of the living room and face this memory straight on. Yet again, my presence goes unnoticed. I am an invisible spectator, not a participant. My father’s clarion baritone reaches my ears as though piped through a speaker.

“And Isaac brought you here?” he says.

“Yeah,” my double says hollowly. “He’s a good guy.”

My father pauses for a moment. His lined umber face is a collage of worry and something subtler, something hard to place. “Do you feel up to telling me what happened? Should we go to the doctor?”

Karina shakes her head with the minimum of required effort. “I don’t know. Probably. They say I was out for a few seconds.”

“Do you know what happened? Isaac got to you after you were down, but did anyone else say anything? It might be hard to remember.” He sniffs at the air. “Is it you that smells like beer?”

“It was a protest for accessible housing. A bunch of students joined in. The Bonneville Association for Accessible Housing.” She paws at a wet patch in her hair. “Some shithead, I saw him and his stupid hat, he was yelling at us, calling us commies and ugly bitches and whatever. Then I guess he hit me with a can of beer.”

My father winces with sympathetic pain. “You’re a freedom fighter,” he says, and in my witnessing, I see, almost for the first time, the flash of pride that beams across his face.

She delicately rests her forehead against her palms. “My head is killing me, Dad.”

He lays a gentle forearm across the nape of her neck. “When you’re ready, we’ll head over to urgent care.”

“Give me a minute.”

“OK, but not too long, Karina. I remember reading you shouldn’t rest after you get hit in the head.”

“Yeah, I should get checked out,” I mutter. “Those fucking cops didn’t do a thing, do you know that? They just sat there in their stupid uniforms with their arms folded. In the car, Isaac told me some of these hardhat guys took a swing at them.”

“Dolay politzei,” my dad says.

“What?”

“Is it too early to tell you I’m proud of you?”

“Proud of what?”

“You’re sticking your neck out for a shenere un besere velt, as your grandma used to say.”

“What does that mean?”

“Velt is world,” my father says. “And shenere is beautiful. So something like a better and more beautiful world.”

“It’s just the right thing to do,” my avatar says. She presses her fingertips into her forehead. “Dad, my head is killing me.”

With almost cartoonish solicitousness, my father kicks into gear. He wraps an old man arm around injured Karina’s slumped shoulders.

“Do you need a coat?”

“No, it’s a nice day,” she says.

He ushers her out like a celebrity lawyer shielding a disgraced actress from the paparazzi. The front door clicks shut, and I am alone once more in the empty living room. I look back along the horizon line, and can just make out the frame of the little metal folding table at the far opposite end of this perspectival expanse.

I jog back along what I can only describe as a spectrum of memory. The groan and creak of the hardwood in my parents’ living room transitions to the thwack of shoe sole against tile. My grandparents’ kitchen is now empty. No kreplach on the stove. Even the smell has morphed into something fusty, like wet wool.

I call out into the small apartment. “Hello?”

There is no answer. Something has shifted in these memories, a rupture, maybe, in the quality of my presence. The horizon is new, the polar spectrum separating my world and my father’s, with a true middle ground where, had I wanted, I could have lingered with one foot in 1950s Brooklyn and another in Bonneville in the mid-aughts.

I pull out one of the chairs tucked under the metal folding table and take a seat. Tacked onto the wall beside me is a black-and-white photograph from Old Country. A bride and groom stand behind a row of grim-faced men and women wearing what looks like dark felt clothing and seated on an unseen bench. It is my grandparents, I realize, on the day of their wedding somewhere in Ukraine. They both smize at the camera, a dissonant display of joviality in the otherwise austere image.

One of the groomsmen catches my eye. He looks to be almost a teenager, poised at the very edge of the bench with a knee extended and a lazy forearm resting on the shoulder of a glum comrade. His coarse curly hair is cropped short, and he wears thin metal-framed spectacles. But he is otherwise a dead ringer for my father, with narrow, wide-set eyes and a sharp gnomon nose. As I stare at him, I am filled with an excited uncanniness. Is he winking at me?

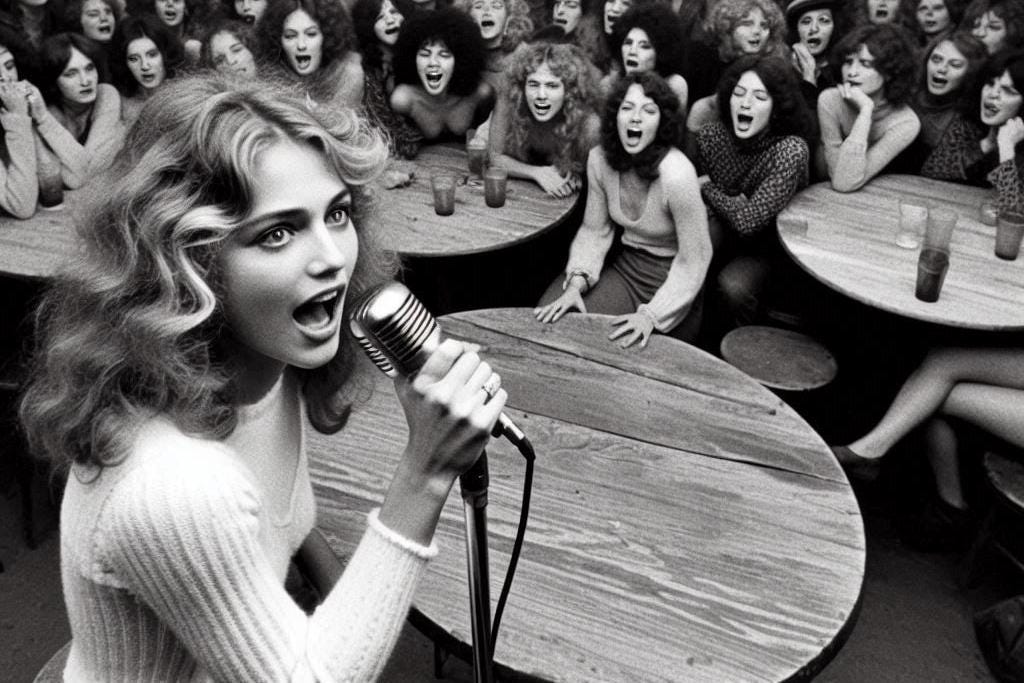

Behind me, there is another shift. I can feel it, almost like a change in air pressure on an airplane. I hear a voice, familiar but somehow fiercer, more fluid. The photograph morphs before my eyes. Where there had been a peasant sitting is now a blown-up portrait of a defiant woman with an enormous, perfectly spherical afro taped to a cinder block wall. I lean back to do a bit of quick reconnaissance. I am now in the cramped rear of what appears to be a coffee shop, with scattered round wooden tables arranged in a loose semicircle around a small makeshift stage on which a woman is gripping a microphone pole and chanting in a poet’s emphatic cadence.

“I am a lioness, you dig? Prowling the Savanna for something delicious.”

There is a whoop from the crowd of raucous women clustered around tables. Some lean in, chins resting on hands. Others crane their necks, calling out in response to the performer. And there, head thrown back, mouth open wide, is an electric vision of my mother sometime after college. She is wearing ultra-high-waisted pants that fall to the ankle. Her face, so eerily similar to mine in my early twenties, glistens under the heat of the incandescent spotlight. She is beautiful, with her wry smile and air of sprightly self-possession, a feminist firebrand on a velveteen soapbox.

“And don’t you shake that mane in my face, Mr. Lion,” she almost growls. “No! I don’t need your protection. I’m plenty ferocious, thank you very much. Plenty independent. Just yesterday, I held my own against a pack of wild hyenas.”

From the gallery, someone bellows an alto, “Yes, you did!”

“Yes, I did!” she echoes. “Right there on the street. I tossed them away like yesterday’s trash. And I am the queen of my pride. And I am proud. I don’t ask, I roar! No fear, that’s right. A lioness on the march.”

There are more cheers and shouts. Some of the young women are on their feet. One blows a kiss at my mother, who catches it with a grasping hand.

“So what is the lesson, my fellow lionesses? Be brave. Be fierce. And for the love of God, stop asking and start demanding!”

She gazes into the crowd and extends a narrow finger into the distance. Her eyes are illuminated like sun on marble. She gestures out into the distance, as though to hail the whole world outside the coffee shop, and I see that the stage floor stretches across an arcing path to a new horizon, where another small figure peeks out from behind a lectern and addresses a markedly more staid audience gazing up at her from auditorium-style seats.

From a bird’s vantage, I could glimpse both poles of this hybrid memory, stretched across a meadow of stage hardwood, twisted into a crescent path, like the terrain of a distorted panoramic photograph.

“If I had a daughter,” my mother continues, “I’d tell her to bare her teeth every now and then, give a little roar. Let the world know you’re here, do you hear me?”

An ecstatic assent ripples through the slam-goers, and I can glimpse, in this dilated moment, the poetry of the emerging juxtaposition. It is me, I assume, the figure at the other end of the telescoping stage, trembling beneath the overhead light, wrists digging into the lectern lip. I remember the mumbled mirror monologues in the speakers’ room backstage, the shock of my microphone-amplified voice, almost tinny in my ears.

It was a performance my mother should have attended, should have exulted in. But had she been there? In my memory, she is conspicuously absent, but I cannot remember why. A schedule clash, maybe, or an introvert’s kept secret.

In the cafe, the assembled women begin to holler and cheer. My mother takes a bow, like a vaudevillian, hands slapping thighs, her cheeks rouged with joy. As she makes her way down from the stage and toward the rear of the space, I rise from my seat to try to intercept her, but a heavyset woman with a wreath in her feathered blonde hair shimmies past my table with an amiable smile to seize my mother by the upper arms. I want to cry out, but the interloper eclipses me with a swing of her immense hips and thunderclap of greeting.

“You killed out there, Mone,” she booms like a gym teacher. “The whole room was electric.”

My mother receives this compliment with the gregarious indifference of a practiced performer. “You think so? I was in a kind of trance or something and just went for it.”

“The lion motif is great,” the woman says. “It got my blood pumping. Kind of Adrienne Rich-ish, but not quite. Do you know what I mean?”

My mother smirks and runs her hands through her silver curls, just like I do. “Oh, come on,” she says with mock seriousness.

The blonde woman grunts and hitches a thumb behind her. She affects an exaggerated, but still very loud, whisper. “Look, Mona, there’s a guy up front who’s been asking about you. Says you two know each other. I told him to take a hike, but he said he was OK waiting outside the door. ‘Just so long as I can listen,’ he said. Nice enough, I guess, but I was firm. Got to keep this place a haven.”

My mother smiles her wry little smile. “He came?” she asks. “Perry?”

The woman shrugs. “Perry, Larry, Harry. I don’t know. He’s still out there, if you want to talk to him. Actually, maybe go outside outside to talk to him. He’s scaring away business.”

“OK, OK,” my mother says. She smooths out her flowy blouse and puffs out her cheeks. “He’s a good guy, Min. I’ll take care of it. I have to give him back his hat.”

She slaloms my table and glides out the door, where the lean, youngish form of my father is sitting patiently, hands folded on his lap, neck craned in dignified interest, ears obviously burning. As my mother approaches, he leaps to his feet to greet her. My mother tips forward for a brief one-armed hug, clavicle to clavicle. Then they exit the cafe, somewhere out of view.

The blonde woman, Min, shuffles up the stage steps and grabs the microphone from the pole, but she is now muted. For the first time, her face comes into full view, the lank blonde hair, round face, snub nose. What is she doing here, in my father’s memory? Around me, the assembled women have stilled in their seats and now appear stiff and glassy-eyed, like mannequins. In my father’s absence, the cafe has become quiescent, a memory on pause.

I peer down along the ribbon of stage floor stretching out from the coffee shop to the auditorium tableau, where semi-filled rows of attendees look on in respectful silence. From the spotlighted horizon line, I can just make out a familiar voice, limpid and confident. I push my chair away from the table and turn my back on the voiceless ur-Min still chattering away onstage. Then I lope across the crescent hardwood plane to the other scene at the far horizon, where I slide into an empty seat somewhere near the front of the auditorium. My antecedent is wearing a wry little smile, I notice, just like my mother’s.

“She said I was an old soul,” rings out the voice of my double. “Inside this body, many others have resided, like guests in a hotel straddling the loops of time. They left an inheritance, it appears, tattered little remnants of the lives they lived.”

The younger Karina captures a lock of silvery corkscrew curls between her fingers like a cobra charmer. “I imagine one is an elder, a sage medicine-woman who has instilled her wisdom in my hair, which springs from my head like coiled snakes. I just have to find it.” She knocks softly on her forehead. “There are others, too. My grandmother led a garment worker strike in New York City in the nineteen-thirties. She comes out, too, sometimes, proof that there is something eternally polemic flowing through me like an electric current. She shouted so that her granddaughter could hear her. No gods, no masters!”

She pumps a fist in the air and then lets it drift slowly back beneath the lectern. “And then there is my mother,” she pauses as though awaiting a response. “Don’t we all carry our mothers inside us? She who was carried carries, too. An inner map bestowed by the womb. What do I call this inheritance? It is not a patrimony, but a matrimony, not a wedding, but a union. Two Xs linked at the centromere. Two bodies with an uncanny likeness that seems to sharpen as we age. And in my family, it is only me. There is no other who bears this maternal map and paternal ink. I suppose that means she lives on through me. Even an old soul has a mother.”

If my mother were here, she would swell with something like pride, or so I imagine. I can almost sense her presence beside me, arms loosely folded across her loose golden blouse, our shoulders nearly touching, the heat coming off her vital, vigorous body, still perfused with blood.

“Who am I?” the poet Karina continues. “This old soul whose forerunners live rent-free in some forgotten corner of memory, leaving muddy little footprints on the surface of her psyche.”

It is the last line I can remember, and so the memory begins to flutter like singed paper in the moments before it combusts into ash. My double’s voice recedes into a harsh hum before going mum altogether. Unceremoniously, without even a moment for me to reflect, the whole scene starts to fade and blur. The audience rises and files out of the auditorium. Their seats flip up and involute into nothingness. The poet Karina and her lectern evanesce under the bright glare of the spotlight, leaving nothing behind but the optic white of evacuated space. The coffee shop has already vanished from the horizon like a desert mirage, leaving only a thin ribbon of hardwood flooring stretching out into oblivion.

“What do you want from me?” I ask aloud, not interrogatively, but with something like supplication. “I’ve had enough.”

The tableau continues to unpack itself set by set. Only a single row of red-padded seats remains, empty but for me and a program draped over the armrest like a stiff towel.

“What now?” I ask aloud. “Hello?” But of course, there is no answer. Just a stirring inside me, something new, pawing at the door of recollection. A new scene shifts slowly into focus, as though directed by a memory stage crew. First, there is a very small, white-walled room. Then a cot in the corner and a folding chair leaning against a rolling stool. A young woman is huddled over a pillow she holds on her lap. She is wringing her hands.

At the dual horizons of this vision, two further scenes unfold like panels of a triptych. In one, the stalking figure of my furious mother looms in the doorway of my childhood bedroom. A perhaps sixteen-year-old Karina glowers back at her from the bed, on which she sits with her arms folded in sullen, impotent rage. In the other, a helmeted Karina careens down a busy street on a clunky delivery tricycle, with an insulated box wedged between the back wheels. I can just make out the emblem of Auntie Ceres’ plastered across the bike frame in blocky print. Vindictive, daredevil cars and trucks swerve around her, this sad-sack figure hunched pathetically over the ungainly handlebars.

I realize in this moment that I can choose one of these panels to dilate, the proverbial three doors. There is something heavy-handed about this mechanism, something contrived. And yet, as far as I can tell, there is nothing connecting these three random memories, whose presence seems apropos of nothing. The only tie that binds, I suppose, is that they are distilled moments of intense experience, generative, rippling happenings that shifted the tides of my life.

One is the setting of the final knockdown, drag-out fight I had with my mother. Its spark was something of such spectacular triviality that I cannot remember it clearly. We did not speak for an entire week before we made up, however, and in the aftermath, I could no longer frame her as adversary. It repels me, this memory, and fills me with disgust. The meaninglessness of my adolescent rebellions, the suffering of burgeoning awareness disguised as boundary challenges. I try to will a curtain to fall over this memory panel, but it simply continues to loop a sort of soundless preview in which my mother and I scream at each other in animated grotesque.

The other panel flanking the hospital scene is the first day of my final job, working for a house plant delivery service, Auntie Ceres’. I shudder in recollection. The alternation of frenetic pace and astonishing boredom. The penalties exacted by the online platform, Be Right There, to which I was yoked like a mule. The humiliation and terror of precarity cloaked in the rhetoric of freedom. It, too, repels me, but not with disgust. It is the shame of the arriviste looking backward, confronting what she escaped. The ghost of a narrowly averted future.

The central panel seems to gleam. Its looping preview depicts a Karina of just six months past entering a small exam room and smiling tentatively at a young woman, who is sitting cross-legged on a hospital cot, hunch-shouldered, her yellowy hair staticky and unkempt and doing good work hiding her face. I fix my attention on this memory, and the scene shifts once more.

The cramped exam room is made more uncomfortable by the musty odour, redolent not of unwashed skin and clothing, but the old vinyl of the cot and stool. I remember this young woman before me, Breonna. I could feel her fear, her defeat, her suspicion. It hung in the air like an impotent warning. At triage, she had reported ten-out-of-ten abdominal pain to the nurse, but refused medication and did not appear to be in agony. For hours, she had lingered in the waiting room like a jacket-draped boulder, knees drawn to chest, head lowered. She was alone, the nurse told me, and reticent.

“Breonna?” I say from the doorway. “My name is Dr. Bergson, but you can call me Karina.”

She does not lift her chin from her chest, but reaches a hand up to her hair, a cheap blonde-ish wig, and draws a handful of long strands over her dark eyes to ensure that I cannot read her expression.

“I’m a resident here in the emerg,” I continue. I close the door behind me and roll the stool out of the corner. The clang of the wheels against a furrow in the stone floor startles her, but she quickly recovers her hunched, inviolate posture. I lower myself onto the cushion, which ejects a puff of fetid air.

“The nurse tells me you’ve got some pain in your belly.”

Breonna uncrosses her legs and draws them up to her chest, clasping her hands over her shins. Her nails are long, I notice, but some of the acrylics are missing. “Yeah,” she says in a muffled voice.

“Can you tell me what happened?”

“My stomach hurts.”

“Can you show me where?”

Breonna shakes her head.

“Or tell me what it feels like?”

Her voice rises slightly. “I told you, I don’t know.”

“That’s OK. Take your time.”

We sit there silently for a moment, and something shifts in my bearing. When we had met in the world of solids, I had peppered her with questions, not aggressively, but with a certain novice persistence. Now, an idea comes to me.

“Breonna, could I grab you a cup of water? There’s a fountain just outside.”

From beneath her coat drape, a thumb rises in response. I lean out the door to fill two large styrofoam cups with crushed ice and cold water. I set one by my stool and offer the other to Breonna, who flicks a long nail toward the speckled stone floor beneath the cot.

“You can just put it there,” she says, and I do as she asks. “Thanks,” she says, almost whispers, as I rise from my squat.

I return to the stool and readjust my stethoscope, which I have tied like a cravat around my neck. From underneath the jacket tarp, an arm reaches down to scoop up the cup. Then Breonna doffs her cape and begins to sip. I know she is in her late teens, but I am again taken aback by her girlishness, the adolescent smoothness of her skin, unblemished under her offset wig. She does not meet my gaze, but conspicuously avoids it with a feigned indifference belied only by the fine trembling of her hands.

“What happened, Breonna?” I ask.

“I told you, my stomach hurts.”

“Do you have an idea of why it hurts?”

“If I did, I wouldn’t have come to the hospital.”

I nod and lean forward in my stool. Two thought streams fork at the convergence of this moment. I know vaguely what I said to this young woman when we met several months ago, but it isn’t what I should have said. Now, it appears I have an opportunity to redress, to replay, to redo. And I take it.

“You know, the human body is an amazing instrument,” I say. “We used to think it was somehow separate from the mind, where we do our thinking. Thoughts and feelings belong to the mind. Pain and the other physical stuff belong to the body. But it’s not true, Breonna. More and more, we’re learning that the body and mind are connected.”

“What is that supposed to mean?”

“Well, sometimes the body raises alarms with sensations like pain. A stomach ache might mean your appendix is ready to burst. But it also could mean something happened, something that you wouldn’t think would cause a stomach ache, but lo and behold, it does.”

Breonna brings her dark eyes to mine and her face softens. “You know,” she mutters.

“I don’t really know,” I say. “But I have a feeling you’ve been hurt.”

She slides her hands to her upper arms in a makeshift self-hug. Then she begins to weep silently with great, racking sobs. I am tempted to embrace her there on the cot, but I resist, even here in this memory space.

“I’m so sorry, Breonna,” I say. “I won’t push. We don’t have to talk about it. But if you want, I can give you some options for things we can do here in the hospital.”

“No,” she whispers. “We can talk about it. But are you going to, like, look? Like, in there?”

“We’ll just talk. But whether you let someone examine you, that’s up to you, Breonna. You’re in control, OK?”

She nods. “I know him,” she says. “Fucking asshole. No one did anything. They let him take me upstairs. They just—fuck. They just kept playing that stupid Playstation game.”

And to my surprise, this time she opens up to me. She recounts the whole story of her assault, which my memory has evidently pasted together from the sexual assault response team note I read the shift after I met this young woman. Earlier that evening, a friend of a friend lured her upstairs at a house party and assaulted her in a bedroom. Afterward, they returned to the party together. The predator was unrepentant. He clutched her hand in his, bragged to the room that she could not keep her hands off of him. In a particularly cruel and debasing display of power, he even announced to the others that it was she who insisted he forgo the condom “for the feels.”

As I listen, I am filled with a queasy kind of rage, a desperate, aching indignation that emerges when one encounters the wounding not just of the human body, but also its spirit. After some discussion, Breonna decides to go through with the rape kit and full physical exam. In a particularly courageous decision, she also decides to file a police report right there in the hospital.

My supervisor, a male emergency doctor, sweeps into the room to ask about our management plan. I usher him outside and suggest we leave the case with the hospital’s sexual assault response team. He concurs wordlessly, and I return to Breonna, who has assumed a more comfortable posture. She is now sprawled out on the cot and nibbling on some potato chips.

“A special doctor is coming to see you,” I say.

“A woman, right?”

“Yep. She’ll be with you for the next few hours. You’ll do the exam, police report, and everything together. She’ll also help you find somewhere safe to go if you need.”

“Nah, I’m good,” Breonna says.

“Do you have any questions for me? Or anything you wanted to chat about?”

She twists her lips and squints. “You’re a doctor?” she asks.

“Well, I’m a resident doctor. I have a medical degree, but I have to do a little more training before I can go off on my own.”

“When is that?”

“End of June,” I say. “If everything goes according to plan.”

“I want you to be my doctor,” she says. “When you become, like, a real doctor. When you’re all set.”

There is a knock on the door, and an older woman with very small round glasses peeks in. She smiles warmly at me and Breonna.

“I just wanted to come in to say hello,” she says. “I’m Dr. Alanna McKinnon, and I’m with the Bonneville SARC.”

To my surprise, Breonna meets her gaze and nods. “OK.”

“I know you and Dr. Bergson are chatting,” says Dr. McKinnon. “I was going to grab something from the vending machines. Want anything? A pop, water, a bag of potato chips.”

Breonna holds up the styrofoam cup and jiggles the crinkly chip bag. “I have,” she says.

“Nothing else you want?”

“No, it’s OK.” Breonna pauses for a moment, and then her pencil-thin eyebrows raise as though she’s remembered an old lesson. “Thanks.”

“Well, I’ll be back in a bit, then,” the older woman says. She gestures at me with two loose fingers. “Good to see you, Karina.”

I offer a little wave of my own, and Dr. McKinnon closes the exam room door with a faint click. Breonna pops an ice pellet into her mouth and crunches it.

“I mean it,” she says to me. “Give me your e-mail or something, and I’ll hit you up in June.”

A smile tugs at the corners of my eyes. “I think you’ll have to look me up,” I reply. “I don’t know where I’ll be then. Karina Bergson. Bee like bumblebee.”

“Like bumblebee,” she echoes. She grabs her coat from the cot and folds it into an amorphous shape before sitting on it. “You know, you did good,” she says, her voice clear and confident now. “This was better than last time. I really felt like you were here for me, like I could trust you.”

“You’re breaking the fifth wall,” I say without missing a beat. “Or would this still be the fourth wall?”

Breonna draws a cigarette from behind her ear and dangles it between her lips. “Take your pick.”

“What do you want from me?” I ask, now so inured to these preposterous occurrences that my tone is almost earnest.

She eyes me impassively and shrugs. “Memory makes and remakes for us a map of the past eagerly leaning over the present,” she recites, seemingly verbatim, from my father’s haunted letter.

“Anything else?”

She lights the cigarette and shakes her head. “You did good, Karina.”

Sensing this is my cue to exit, I make my way out into the undulating maelstrom of the emergency room hallway. Scattered clusters of patients obstruct the thoroughfare. They moan in cots and fidget in chairs set hastily askew. ER nurses bustle through, some young, their hair yanked into tight ponytails and secured with athletic headbands, others battle-hardened and seam-faced, the veterans of a never-ending welter.

It is the ER as I remember it, chaos just barely contained, a pure cross-section of the medical universe, where quite literally anything can happen: massive traumas, first presentations of cancer, lithium batteries in noses, syrup bottles in rectums.

Beside me, an elderly woman lying supine on a gurney wails. Her crinkled hands rest impotently on her abdomen. I recognize the guttural, throaty yowl as a kind of begging, a grey-faced plea to the gods. Hers is the call of death. I remember it from my very first rotation in clerkship, when I met an elderly Italian woman with ischemic bowel. My supervisor that day, a severe and morose general surgeon, made sure I took note of her agony.

“Next time a patient tells you they have ten-out-of-ten pain, think of this lady,” he said. “Pain is subjective my ass. Look at her.”

The woman in the hallway shifts in her gurney, and I discover that she has shape-shifted. Her legs are splayed under her faded hospital gown and she is bulbously pregnant. Beside her, a child, ostensibly someone else’s, clutches his elbow, below which the jutting bone of his radius erupts through the smooth brown skin of his forearm. He stares straight ahead, his face a mask of shock, perhaps, or simply frozen in place. Further into the wild ferment of sickness and injury, the domed fluorescent ceiling fixtures stretch some ways into the abyss, but there is something on the horizon, a patch of evergreen rimmed with light so resplendent that I have to avert my eyes. I dance and twirl through the throngs of hard-bitten nurses and meandering, dislocated patients.

At the hallway’s farthest frontier, a small courtyard comes into incongruous view. The gritty institutional sheet tile coalesces seamlessly into the soft floral groundcover, which unfurls out toward a deep, verdant horizon. A quick backward glance reveals the entire interior of the emergency room. The facade has been peeled open like an orange, revealing a dense matrix of curtained exam cubicles and modular nursing stations filled with frenetic bodies in constant motion. But when I turn toward this new scene, the din and tumult recede to a hum, as though I am shutting a colossal door.

Nearest me, where the sheet tile of the emergency room hallway gives way to an expanse of close-cut clover, is the solitary figure of Ben. He is bedecked in pumpkin cords and a linen shirt the colour of whipped cream. Absently, he strokes a stubbly cheek with the flat of a fingernail while he listens squint-eyed to a spectral someone who is evidently quite captivating. Beyond him, doppelgängers from the dankest, remotest corners of my memory wander haphazardly around the plaza, bumping into furniture set askew, bombinating in murmured conversation, gesturing with the artlessness of aliens who learned human mannerisms from a manual.

“So, what the hell’s going on here?” I demand. “What do you want from me?”

Ben pivots on his deck shoes and fixes me with a sheepish little smile. “I did tell you to ask that.”

“Well?” I ask. “What’s the answer?”

He shrugs and plunges his fingers into his shallow cord pockets. “You’re going to have to tell me.”

“Who were you talking to?” I ask.

He frowns at this question. “This is a silly kind of game we’re playing.”

“Let me guess,” I say with a smarmy smile. “Me.”

“You sure I don’t need to shake you or anything? Make sure you don’t get lost in your trance?”

“Ta da,” I say. “I’m here already.”

He stares at me blankly, like a robot having an electronic stroke. “What?”

“This is it, the turning. And I’ve been here for a long, long time. I assume you’re here for a reason, right? Tell me, what am I supposed to do now?”

He shrugs and turns away from me to engage his spectral interlocutor once more. It appears we have reached the end of his script, this hollow Frankenstein of memory and minutiae, accurate down to the micro-gesture. There is a part of me that is relieved to see him, and yet he is not actually Ben, but some sort of purposeless memory composite, ersatz and flat. We barely know each other, I realize, and so in recollection, I cannot generate anything more than the shallowest verisimilitude.

I turn from him without another word and stride into the thronging middle of the space, thick with offset medical equipment and the sundry cast from my training drama. There, immured by a tangle of mobile computer stations, I can just make out the odious figure of Dr. Fossal, who leans against a three-legged stool and runs a stubby finger along one of the monitor screens, blissfully oblivious of her cloister. A contingent of nurses I’ve known, malevolent and saintly alike, meanders through the debris and toss eye rolls and mouthed “I knows” at one another in a bizarre pantomime. My fellow residents are there, too, including Rhiannon, with her cinched scrubs and tight ponytail and boxy bright smile. It appears she has brought her morose nemesis with her, Dr. Schumacher, flapping an invisible newspaper as he leans precariously against a ghost wall, his stupid gossamer hair plugs quivering like cotton candy in the still air of this otherworldly space.

Like a thief in a laser-guarded vault, I gingerly step over shrubs and a few supine, grasping patients plucked from the depths of my remembrance. I call to Rhiannon.

“Hey, what are you doing?”

She grins at me and gallops over. “I can’t believe I’m on with Schumacher again,” she says. “That fucker.” She gestures toward her foe down the way. He presses the blade of his hand into his crinkled forehead to survey the course on which he is ostensibly now golfing.

“Why are you here?” I ask.

She scoffs and feigns exasperation. “Don’t you want to be a doctor?” she says in her patented impression of her father Pan. “Every parent—I mean, child—every child wants to be a doctor. Reach for your dreams!”

I try again. “No, Rhi. Why are you here right now?” I clasp her shoulder and gesture at the discordant snarl around us. “Can’t you see?”

Like Ben, she is stultified, vacant, like a child having an absence seizure. Five years of intense, intimate friendship reduced to a regress of banality and nonsense.

“Forget it,” I say, and twirl past her, almost colliding with Faisal, the emerg resident who received me after my father’s accident.

“Sorry, Faisal,” I say reflexively.

He brushes my arm with a solicitous hand. “No,” he says. “I’m sorry. We’re here for you.”

I dance through the welter of patients and fellow medicos, avoiding the hunched and maleficent figure of Vera Borsuk perched like a wounded hawk on the seat of her walker. I smile at Ms. Halfpenny, who is jogging in place in blissful unawareness of her fixity in space. I keep a brisk pace, cantering along the pitch, shoving mobile computer stations out of my way, stepping over IV poles, wading through a patch of clacking terrain that, on closer inspection, is revealed to be a shallow moat of pagers and their cheap plastic casings. At the edge of this black morass, a battered delivery tricycle is parked, its front wheel just kissing the scuffed screen of a cracked pager. The insulated delivery box is nowhere to be found.

For a moment, I feel I am sinking, but it is only the awkward transition back onto the soft, springy groundcover. Here, wilted houseplants in chipped ceramic pots erupt from amid a bizarre assortment of bric-a-brac strewn across the panorama as though dropped from an airplane. Stray school desks lay overturned. Dorm beds upended. This, I gather, is an outlandish microcosm of the vast middle of my still-young life, the cascading, electric years of youth that stretch from the awakening of childhood consciousness to the halcyon end of university. Marcel, my French fling, and Jake, my college boyfriend, confer closely as I pass. I can almost smell the detergent of their jackets, both denim, I notice. They seem to be leaning against a thick wooden door that leads nowhere. I strain to glimpse the placard, almost obscured by Jake’s melon head, and sure enough, I can just make out Swann Memorial Lecture Hall, where I spent most of my first year of university.

I make my way to the nearest grassy promontory, from which I can survey the whole expanse. There appears to be a logic to the madness, a wry chronology snaking outward like a Bildungsroman read backward, the gauntlet of a life lived in reverse. Behind me, my medical past leans over a shaky present. Ahead of me, the depths of my past unfurl in lunatic disarray. I cannot help but wonder if I am like Persephone, wandering through Hades at the behest of her father. Onward I go, bushwhacking through the thick, swelling desolation of dead memories because I have no choice.

I stumble past Jake and Marcel without a second glance and kick a pillow tossed, I imagine, from a dorm bed and onto my path. Past my erstwhile lovers is a pool of crumpled paper. I lean down to retrieve one of the spiky balls, like an abstract sea urchin, and open up the page to reveal a diagram of the Krebs Cycle. Another is a scrap of Rilke: “She moves the way clocks move. And on her face, as on a clock dial which someone shines a light onto at night, a strange, briefly shown hour stands: a terrifying hour, in which someone dies.”

In which someone dies. I hurry around the pool of lost pages and some of my old professors, who scoop up the paper into what appears to be gold panning dishes, prospecting in what is quite literally a sea of knowledge. Something is now buzzing in my ears. It is a sort of hum, intensifying with each step. Even before I spot its source, I recognize the intoxicating, rhythmic sound of chanting in the distance. Dotting a clear path forward are protest signs set on pikes hammered into the soft earth.

No Blood For Oil!

Housing Is A HUMAN Right!

Which Side Are You On???

Daloy Politzei!

I expect to come across a crowd, but instead encounter a lone figure, looming like a sentinel on an abandoned battlefield, his straight back and stentorian roar the last vestiges of the military machine that broke him.

“Hey hey, ho ho! This racist war has got to go!” he bellows and thrusts a tight-knuckled fist into the air.

The memory machine has exhumed an obscure memory, indeed. There is Isaac, my valiant protest comrade, who had deposited me onto my parents’ couch all those years ago, when a disgruntled slack-jaw in a pickup brained me with a full can of beer. Even in recollection, he was silhouetted, almost incorporeal. Was it my father’s memory or mine that was reenacted across the horizon line? I no longer know.

Isaac was a regular, I remember, rangy and hardscrabble, a decade or so south of middle age. A lot of us were poseurs and we knew it, college kids with big ideas and only enough courage to not quail at shouts from car windows. But Isaac was the real deal. The rumour was he was radicalized in Afghanistan, our Gen X Ron Kovic. He meant it, we could tell. Though I remember little about the man, his dented silver Pontiac is emblazoned into my consciousness, always parked just down the street from the protest, under the lushest tree around, with an iridescent windshield shade spread aslant by hurried hands.

We never spoke about the incident, Isaac and I, though I saw him at countless other protests. He always greeted me with a nod and stone-faced smile, the almost imperceptible lifting of those hollow cheeks. And, I realize suddenly, I merely nodded back. No acknowledgment of his act of kindness. Never a thank you. Just the facile assumption that he understood, by some transitive property of intention, that I was grateful he intervened.

Presently, this seems a grave lapse. I approach him sheepishly, like a treacherous friend after a drunk argument. “Isaac.”

He pauses mid-bark and blinks at me in greeting. “All right there, Karina?”

“Do you remember when that piece of shit in a pickup truck knocked me out with a beer can?”

He clicks his tongue and closes his eyes. “Just drove away, the coward. Yeah, I remember.”

“You dropped me off at my parents’ place.”

He nods and lets his sign, which reads You Lie Kids Die, rest on the top of his boot. “You don’t mess with concussions.”

“Well, it was a good thing you did,” I say. “And, you know, I never said anything to you.” I can see him start to shrug, but I hold up a peremptory hand. “No, Isaac, it meant something.”

He fixes me with his heavy, steady gaze, somehow both empty and overflowing. “Don’t mention it.”

I grab his hand, with its rough, almost scaly skin. “Is there anything you wanted to tell me?” I ask. “Is that why you’re here?”

He shrugs again, but this time I allow him to complete the gesture. I sense I have reached the limit of his capacity, this memory of a man I never really knew.

“That’s it?” I ask disappointedly.

He hefts up his sign and lofts it skyward. “Whose streets?” he demands.

“Our streets,” I mumble to myself, deflated.

Back along the long road I go. The relentlessness of these inane, soulless interactions slows my pace some, but there is something tugging me forward, an imperative to reach the end, wherever and whatever that is. The rest of my university years tumble out before me in ludicrous metonymy, bridges of cracked whiteboard and heaving naked bodies, whose partnerless thrusting into the open air is equal parts acrobatic and asinine. There is even a technicolour mushroom patch pulsing under a dancing tree.

Just ahead of me, a sort of Maginot Line emerges, a partition between orgiastic and awkward. A full orchestra fills the interstices left in between overturned lockers planted in the earth like hedgerows. The music stands, I notice, appear to be cafeteria trays floating in the air, and the piece is classic band boilerplate, all shouty brass and whistling woodwinds.

The apoplectic figure of Maestro Holland, red-faced and crazed, bellows his spittle-flecked notes to the be-pimpled trombone section, which empties what seems like a bucket of “condensation” from their spit valves into a nearby tuba bell. Conspicuously absent is the first bassoon, I notice, though it does not take long for me to spot a bocal threaded through the punctured pocket of a lacrosse stick, whose frayed strings wave like a white surrender flag in what appears to be a pile of Karina’s abandoned extracurriculars.

At the rear of the orchestra is Charlotte, my closest high school friend. She is standing before a marimba, her small mouth held in miserable rictus as she attempts to keep tempo. One of her eyebrows is obviously darkened with pencil, a casualty of errant waxing. She mouths to herself in apparent panic and looks around wildly as the maestro smacks his fat hand against the levitating conducting lectern.

The noise is tinny and uneven, as though heard through badly fitted earplugs. Exactly, in fact, like the orange cones that strained against the muscular, uncontrolled trumpet chorales all those years ago, when only fortissimo would do. I step over a bleacher bench to circle around to the percussion, where poor Charlotte has now moved on to a gong, which she strikes an eighth-note too late. I have not spoken to her, my erstwhile confidant, in more than ten years. Last I heard, she had become a lawyer in Gatineau.

I tap her on the shoulder, and the din recedes almost to a whisper. She greets me with a big smile, more bracket and band than tooth. “Kar, this piece is totally hard.”

“What ever happened to you?” I ask.

She rolls her eyes and sighs. “Oh, my God. Ian is such a brat. He made me take the marimba and he stayed on the timpani because he thinks he’s all that and a bag of chips.”

“No,” I persist, flailing against the futility of the inquiry. “I mean, why didn’t we stay in touch after high school?”

She replies with a non sequitur. “I have debate after school, but we can hang after. I’ll call you.” She reaches out a hand to brush a gray curl behind my ear. “I love your hair. Mine’s so, like, fine, but you’ve got those curls that go bounce.”

Those curls that go bounce. Is that what remains? “I should have called, Charlotte,” I say, almost to myself, and I leave her there, hovering beside the gong.

And onward I go. Further down the path, fallen, sticker-laden shelves lay cracked and splintered on crumbly earth, stacked with dusty paperbacks and unmarked VHS tapes and God knows what else. Even in this memory topography, it seems much of middle school is exiled, tucked away, relegated to the hinterland of recollection, where it belongs, nothing more than the unfortunate frame for the romantic, woodsy panorama of my endless camp summers. An expanse of lake, like a gigantic clipped fingernail, glimmers in my foreground, beyond which I can just make out half of a gaga court, where my first swain, Micah, slaps a textured red playground ball through his splayed legs.

“No, you’re out,” I hear him shout with adenoidal adolescent authority. “Goddamn it, Ari, that’s not true. I saw it hit you right in the leg.”

There is a part of me that wants to approach him, but even here in this other place, it feels unseemly for the adult Karina to banter with this young teenager with whom she experienced a world of firsts. Instead, I call to him from across the lake, much like I would have twenty years ago. I cup my hands around my lips and yell in my hollow treble.

“What ever happened to you?”

Micah scoops up his bouncy red ball and scans the landscape. “I didn’t tell her that,” he calls back in clanging dissonance. “Danny did. He’s a loudmouth.”

I amble past the camp scene, but steer clear of a roving band of false friends and an oversized school desk that drips crimson blood onto a pile of Air Jordan shoes. Even now, I am mortified by this image, magnified to a grotesque of abject shame.

And then the scene becomes stranger still. I soon come across a kickball game, where my first friends are playing against an assortment of Saturday Morning cartoon characters whose names I can no longer remember. A scale model of the Aggro Crag looms in the background. Rockapella’s dulcet barbershop is piped from an unseen speaker.

My grizzled old dog, Lucius, is hovering before a freestanding white wall, transfixed and coiled like a spring, his snout oscillating before what I can only imagine is a rogue sunbeam. His grey fur has almost a blue hue in the blazing summer sun. When he sees me, he trots right up to my shins for a sniffed greeting. This act of agency takes me by surprise, and I gather him up in my arms to bury my face in his fur, which, as always, smells inexplicably like Fritos.

We drift along together, now, just as we always did, going God knows where. Lucius stops to sniff the shrubs, off of which plastic-wrapped chapter books hang like fern fronds. Every few steps, it seems, another wondrous, vivid theatre of pure experience emerges fully formed before us. The latest is the cavernous rear of a grocery store I toured as a child, peeled open like a geode, with a colossal walk-in freezer whose frosty shelves appear to stretch into the sky.

Lucius trots ahead some ways and then bends his woolly head to gingerly fetch an object from the grass. He brings it back to me and drops it at my feet, a single yellow vinyl children’s rain boot. I use my hand as a visor to scan the horizon, and just as I might have predicted, fat, sullen rainclouds are gathering over a single clawfoot bathtub.

The grass gives way to sticky tile, along which Lucius skitters with his usual abandon. Ahead, a perfect facsimile of a burgundy Finkelstein’s booth comes into view. There are my mother and father, nearly intertwined at its centre, with their relatives flanking them like the apostles at the Last Supper. Each of my parents holds a half-eaten round of an everything bagel, on which they nibble between red-faced peals of joyous laughter. I do not even have to call out. They anticipate our approach, hailing us with waving hands and unintelligible inducements. But before I can reach them, there is a crack, like thunder, which vibrates the tile underfoot. With a yowl, Lucius bolts from the scene, back whence he came, and soon vanishes out of sight.

The rest of my family, grandparents and aunts and uncles, rise from the table. They file out of the deli and into the dense thicket beyond this final memorial boundary. My mother takes my father in a tight, terrified embrace, and then something, some spectral force, wrenches them apart. The long wooden table splinters into two jagged halves, which hurtle in opposite directions. Then my parents’ limp frames are cast to the far poles of a burgeoning panorama that comes into slow focus. At one end, my waning mother is lying under a matte blue duvet on the sagging old couch in my parents’ living room. At the other, my elderly father is splayed across a hospital bed with a jagged red asterisk of blood mushrooming across his bald head. They are separated by a diaphanous curtain.

Behind me, the landscape of memory has now disappeared, leaving in its absence a never-ending plane of optic white space. I want to cry, but my tears are dammed by a towering wall of dread. I try to scream, but I have no voice.

My mother coughs shudderingly into a tissue, which she presses into her lips. “Perry?” she croaks. “Perry? There’s blood again. A lot of it. Call the ambulance.”

*Note: The illustrations accompanying this story were generated using AI technology. I’ve left them as a sort of cyber-hairshirt. Please read my repentant anti-AI mea culpa and, if you can, forgive me.

I really enjoyed the dream-like quality of this - it is beautifully written.

All of those experiences being remembered painted such an incredible picture of Karina and her family's history. I found myself deeply attached to the family simply after finding out that he father had been a protester for equality.

This was gorgeously executed - just such beautiful writing.

🦁